Latino Immigrants Face an Uphill Battle to Economic Inclusion

This blog post by Angel Ross was first published on the National Equity Atlas August 9, 2016.

Immigrants have been an integral part of the social, political, and economic fabric of this nation since its inception. But increasingly hostile local, state, and national policies and climates put many immigrants in precarious situations, restricting both their participation and potential, and ultimately hurting the economy as a whole.

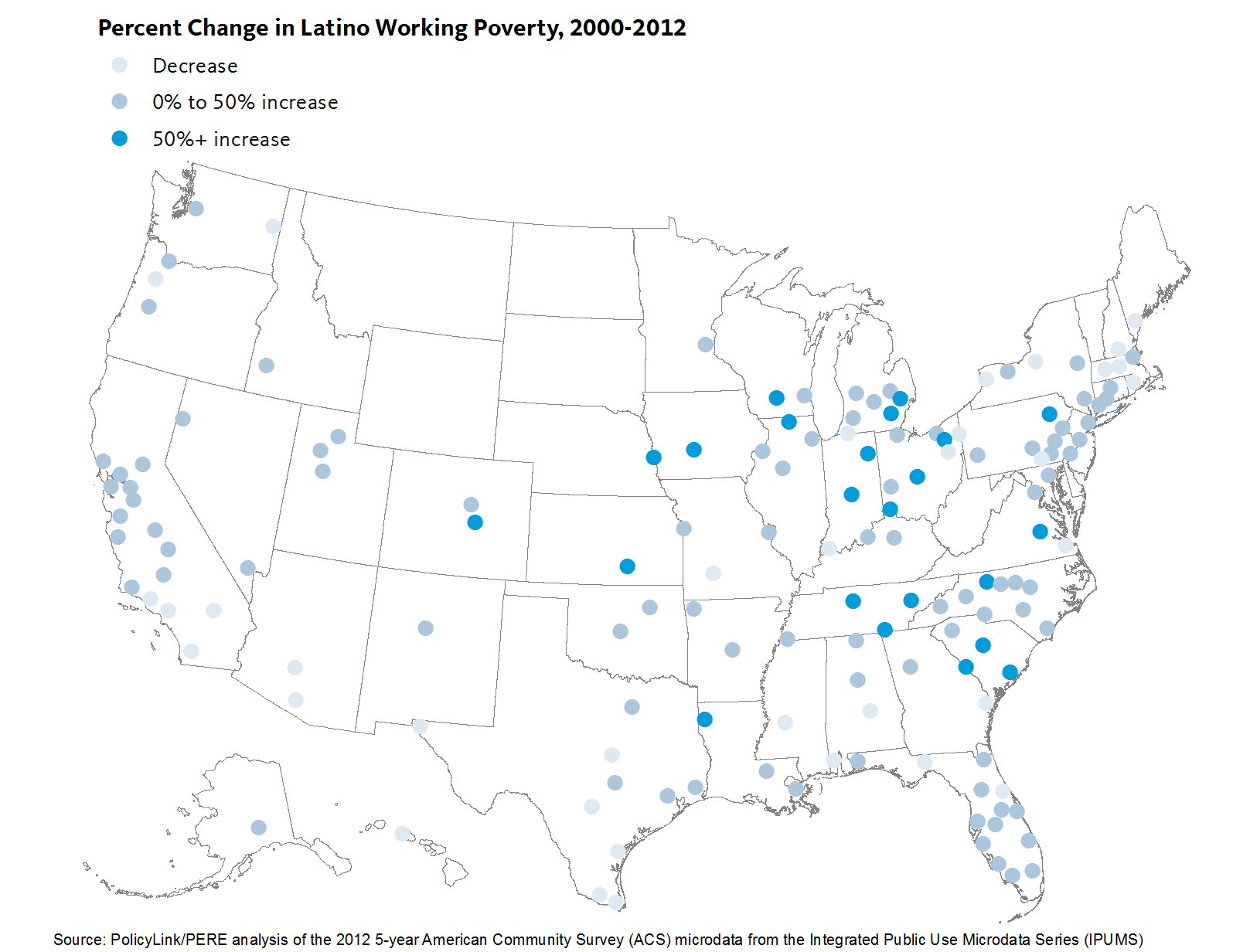

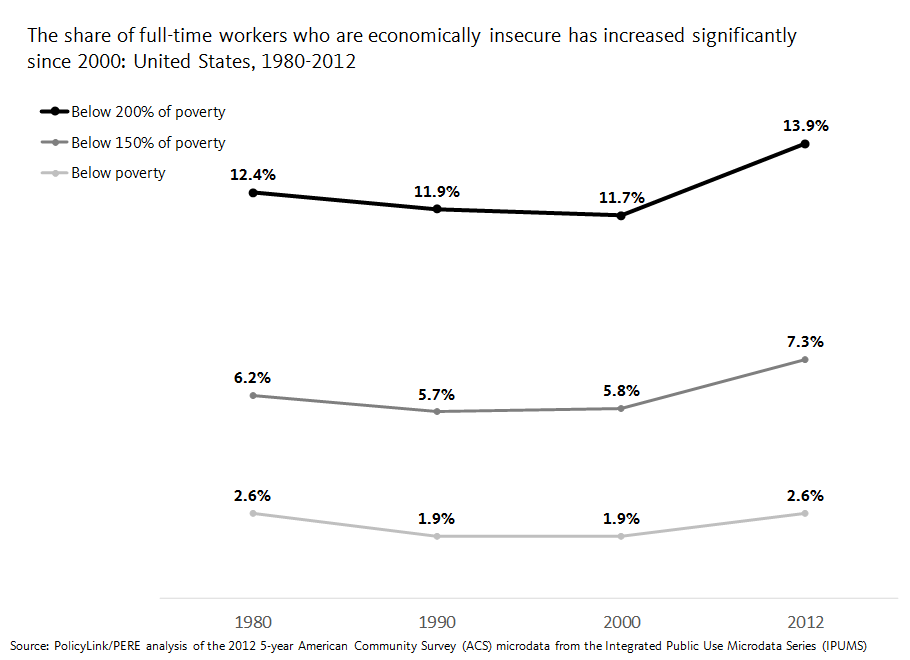

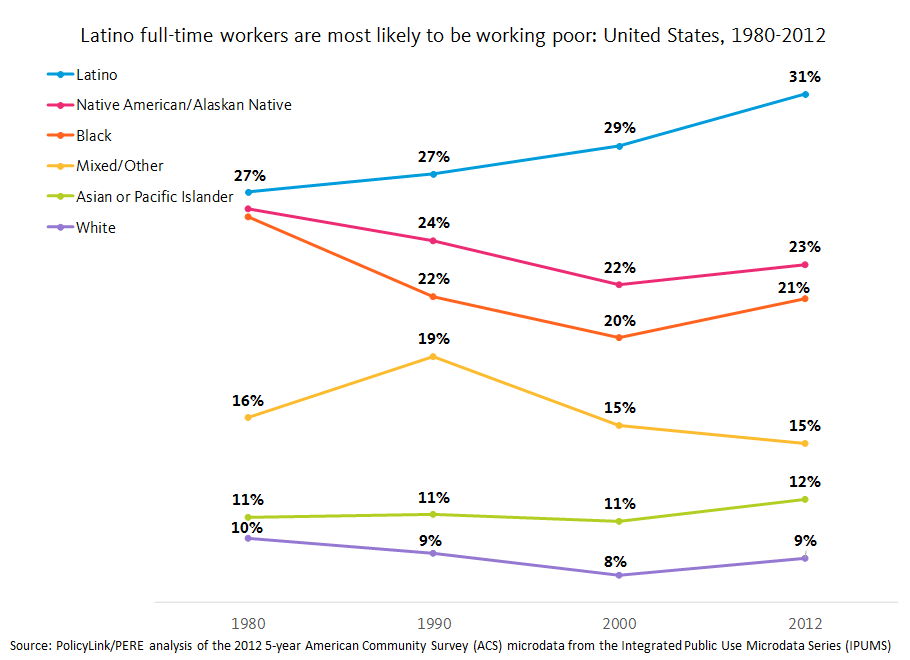

In June, we released data on working poverty in the Atlas, and found the number of Latinos working full-time yet still struggling economically has increased steadily over the last three decades. Last week, we added breakdowns on immigrant status to eight Atlas indicators, including working poverty. This new data reveals the significant challenges of working poverty among Latino immigrants and the vast differences within the Latino immigrant and U.S.-born populations. For instance, nationwide Latino immigrants are twice as likely as U.S.-born Latinos to be working poor.

This analysis describes working poverty among Latino immigrants, examines the cities with the worst outcomes on this indicator, and highlights policies to support immigrant integration and ensure economic security.

Employed Latino immigrants have higher poverty rates than U.S.-born Latinos

One in four Latino immigrants between the ages of 25 and 64 is working full-time but has a family income below 200% of the federal poverty level, compared with just 12 percent of U.S.-born Latinos. Mexican immigrants, who account for more than half of all Latino immigrants, have the highest overall rate of working poverty among Latinos at nearly 29 percent followed by Guatemalans (28 percent) and Hondurans (26 percent).

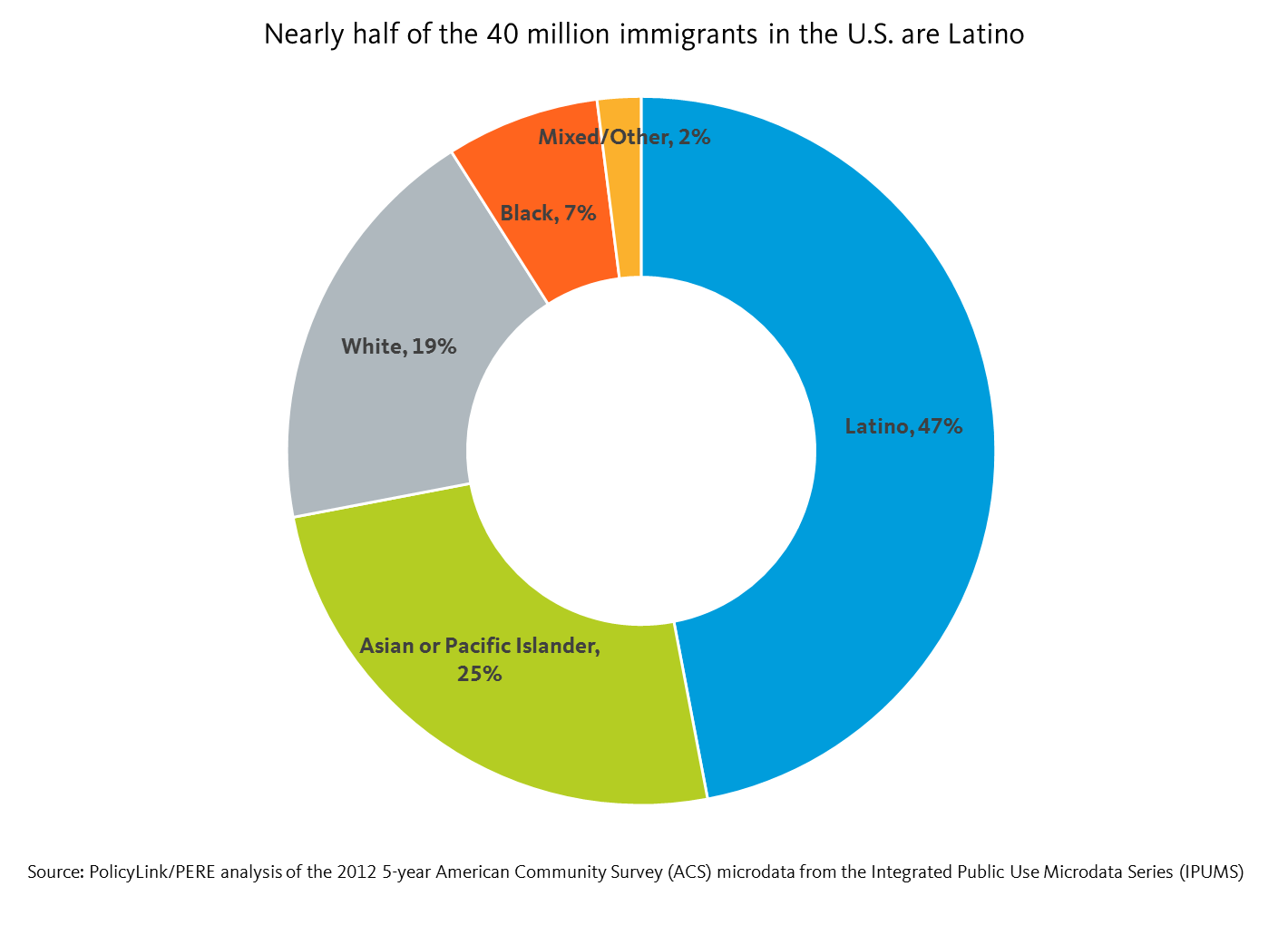

Multiple factors contribute to these numbers. In addition to lower wages and lower levels of educational attainment on average, another important reason is that immigrants, half of whom are Latino, are less likely to be enrolled in public benefits programs. Poverty is calculated based on family income, which includes earnings as well as sources other than work like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF). Undocumented people are currently ineligible for many of these programs, but we see lower rates of enrollment even among eligible immigrant families. Increasing enrollment in these programs is one way to ease the burden that many low-income immigrant families face in the U.S.

Many immigrants are also part of mixed status families, which might include authorized immigrants, undocumented immigrants, and U.S. citizens. By 2010, close to a quarter of all children had at least one immigrant parent. But due to the precarious status of undocumented workers and discrimination against Latino immigrants, exploitation and wage theft is rampant.

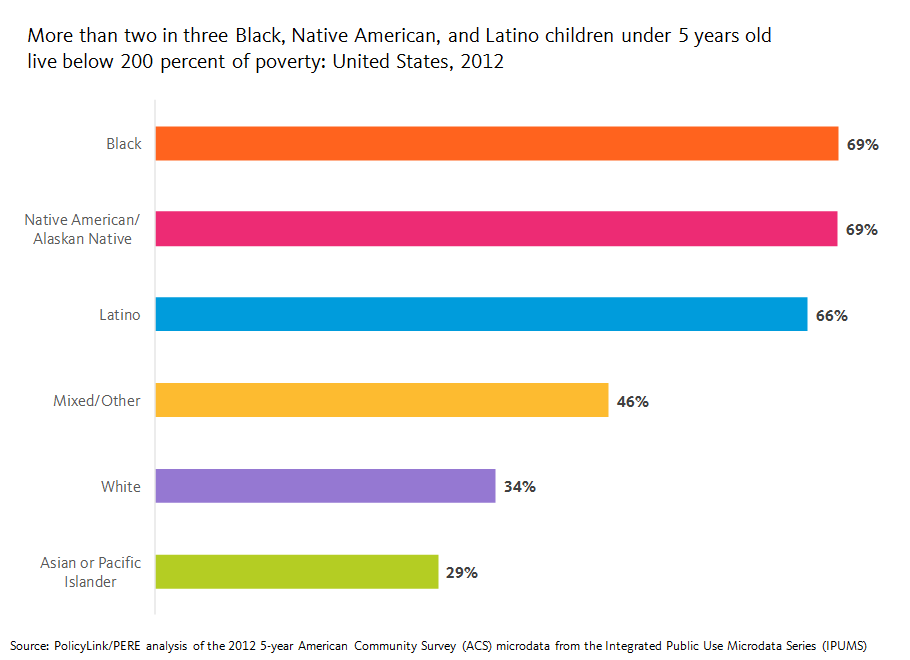

The high rates of working poverty among working-age Latino immigrants translates into high levels of economic insecurity among Latino children, who are a large and growing segment of our future workforce. Nearly 63 percent of Latinos under 18 years old live below 200 percent of poverty as do two in three Latino children under 5 years old.

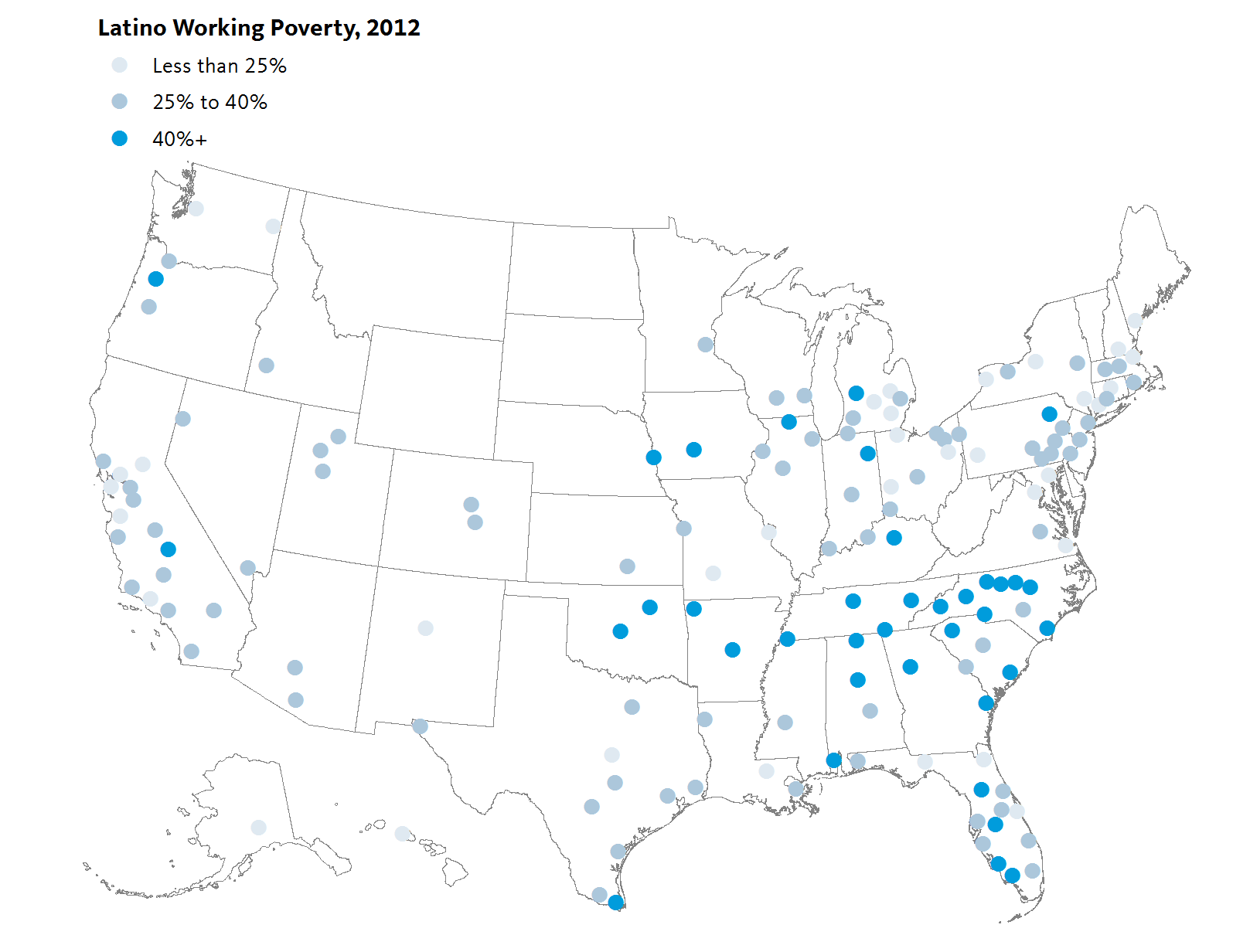

Where do Latino immigrants face the biggest barriers?

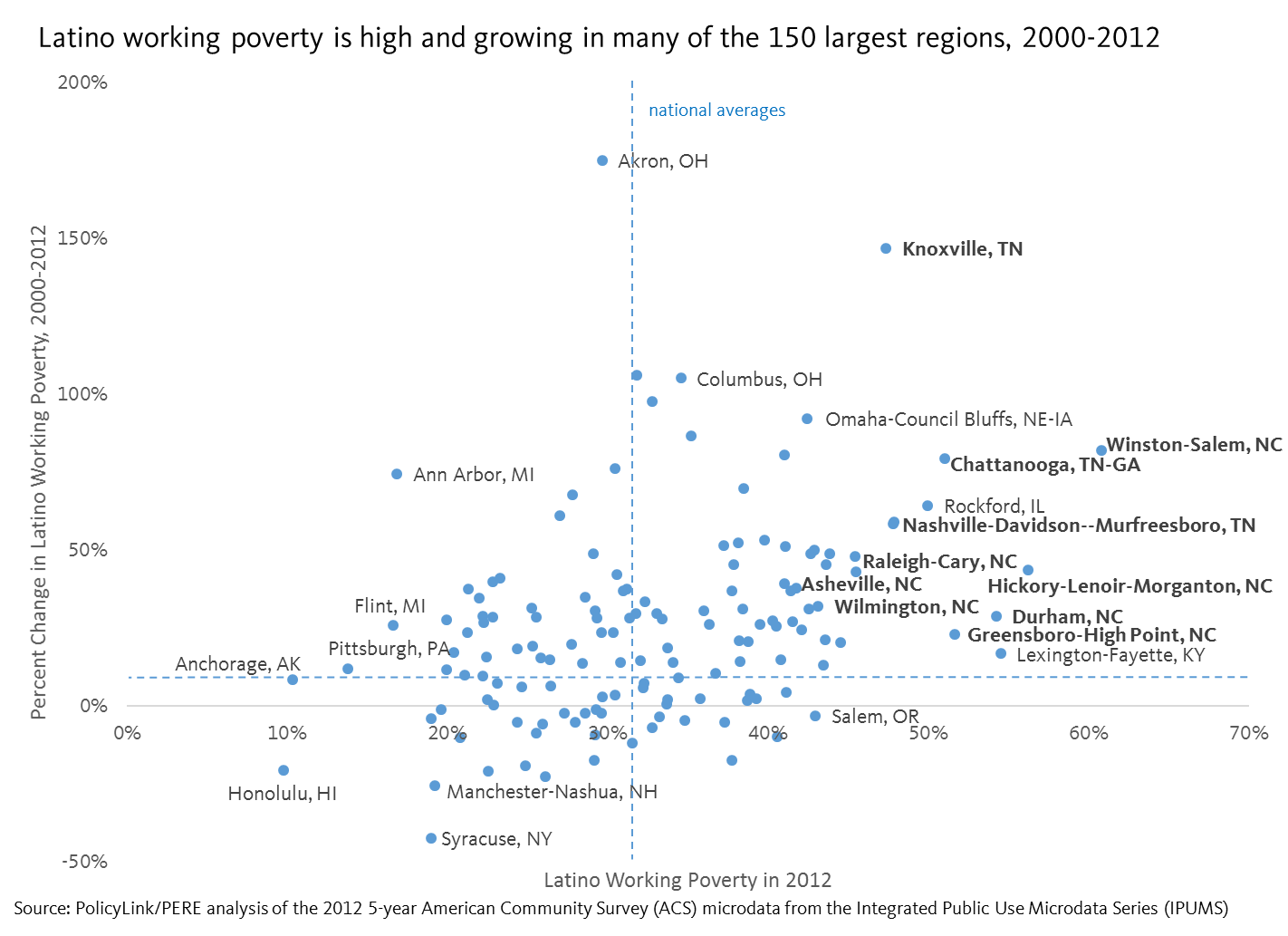

To better understand the geography of economic insecurity among Latino immigrants, we ranked the 100 largest cities in the U.S. by the rate of working poverty and the median wage among Latino immigrants. Because both citizenship and education are associated with higher earnings, we also looked at the citizenship rate and the percent without a high school diploma.

The cities with the highest levels of working poverty among Latino immigrants—with 38 to 40 percent of their Latino immigrants working poor—included the North Carolina cities of Winston-Salem and Greensboro, along with the Texas cities of Dallas and Irving, followed by Minneapolis, Minnesota. These cities also had lower median wages, lower levels of citizenship, and lower levels of educational attainment than Latino immigrants nationally. The national citizenship rate of all Latino immigrants, for example, is 30 percent and the median wage for full-time workers is $12.70/hour. Yet the citizenship rate among the five cities with the highest levels of working poverty ranged from 11 percent in Winston-Salem and Greensboro to 19 percent in Irving. The median wage ranged from $9.40/hour in Winston-Salem to $10.70/hour in Dallas. Similarly, just under half of Latino immigrants nationally lack a high school diploma, but that number goes as high as 68 percent in Dallas.

The cities with the lowest median wages among Latino immigrants—ranging from just $8.90/hour to $10.20/hour—are Raleigh and Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Indianapolis, IN, Plano, TX, and Columbus, OH. Indianapolis has the third lowest median wage but a significantly lower rate of working poverty than other cities. The wage difference in Irving and Plano, Texas show the extent to which labor markets are truly local: the median wage is more than a dollar lower in Plano than in Irving or Dallas even though both are part of the Dallas metropolitan area and educational attainment is higher in Plano. Importantly, Latino immigrants as a whole account for a much smaller share of the total population in Plano than in Irving (7 percent in Plano versus 20 percent in Irving).

Winston-Salem, NC is the only city ranking both in the top five on working poverty and in the bottom five on median wages. With roughly 36,000 Latinos, 20,000 of whom are immigrants, Winston-Salem is home to the largest share of Latinos out of all big cities in North Carolina while neighboring Greensboro has one of the smallest shares of Latinos. Yet in both cities, Latino immigrants face significant barriers to economic inclusion. Four in ten Latino immigrants ages 25 to 64 in Winston-Salem and Greensboro are working poor and half earn less than $9.50/hour in Winston-Salem and $10/hour in Greensboro.

Latino immigrants in the capital of North Carolina at the heart of the Research Triangle (anchored by North Carolina State University, Duke University, and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) have the lowest median wage for full-time workers of the largest 100 cities and even the largest 150 metropolitan areas in the country. With more than half of Latino immigrants in Raleigh earning less than $9/hour, combining the income of two working parents still doesn’t add up to a living wage for a family of three or four. Latino immigrants are more than three times as likely as U.S.-born Latinos in Raleigh to be working poor.

Interestingly, the median wage of Latino immigrants in Durham, also in the Research Triangle, is nearly $3/hour higher than in Raleigh even though a higher percentage of Latino immigrants in Durham lack a HS diploma and the citizenship rates in both cities are nearly identical. The Latino population also accounts for roughly the same share of the population in both cities, but Durham is majority people of color and Raleigh is majority White. Despite the higher median wage, 29 percent of Latino immigrants in Durham are working poor.

Municipal IDs and the state preemption of local policies benefiting immigrants

The North Carolina economy relies on immigrant labor, but last year Governor Pat McCrory signed a bill banning local governments from establishing “sanctuary cities” and preventing government agencies from accepting local or foreign-issued IDs. The mayor of Greensboro viewed this legislation as targeted towards their local efforts to welcome immigrants with one of the first programs in the South that offered ID cards to immigrants. Law enforcement officials successfully pushed back last year and the law only bars city officials from accepting the ID cards, not police or hospitals.

But this year, new legislation was introduced in the state that would prohibit law enforcement from accepting municipal IDs. This law was passed in spite of evidence that local ID cards help to foster a sense of community among all residents and that law enforcement has actually solved more cases due to increased trust from the undocumented community. This type of state preemption to local authority is a threat to equitable development, but continues to gain momentum across the country, particularly in more conservative states, curbing the ability of local leaders to build inclusive and equitable cities.

Immigrant integration is a moral and economic imperative

In an increasingly hostile political environment, one promising strategy for immigrant integration is increasing naturalization. Not only does naturalization strengthen democracy through voter representation, it also results in economic gains. A recent study by our partners at the Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration found that reducing the eligible to naturalize population by half over 5 years is estimated to result in a $75 billion gain to the national economy over ten years. Ending the criminalization of undocumented immigrants by providing a pathway to citizenship and increasing citizenship supports for authorized immigrants has benefits extending far beyond the immigrant population.

In additional to municipal ID cards, other state and local strategies include providing access to health care for undocumented people, as SB 10 did in California, and separating local policing from immigration enforcement as HB 13-1258 did in Colorado. Policies that contribute to the just and fair inclusion of those residents who are often left behind help to create thriving and sustainable communities. To learn more about these policies, visit our immigrant contribution to growth indicator.

To explore data on immigrants for your city, region or state, visit the National Equity Atlas. For more information on the nativity cuts, see our previous blog.

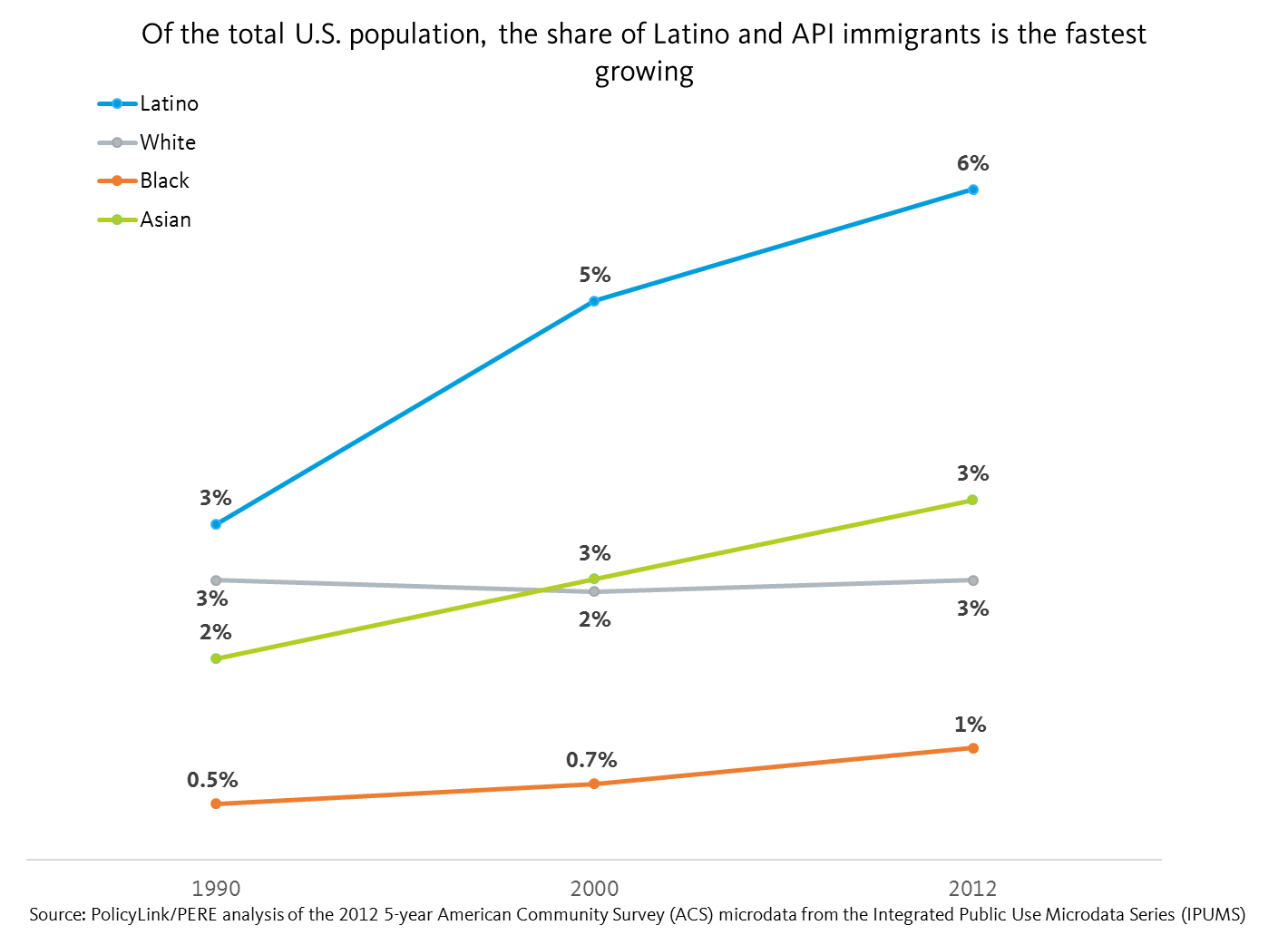

Latino immigrants made up 3 percent of the total U.S. population in 1990, a figure that doubled to 6 percent by 2012. Latino immigrants represent not only the largest share of immigrants in the U.S., but also the fastest growing. The API immigrant community is the second fastest growing and represent 3 percent of the total U.S. population as of 2012. White immigration has more or less stayed stagnant at 3 percent between 1990 and 2012. Finally, Black immigrants make up the smallest share of the total U.S. population at 1 percent, and are not growing as fast as their Latino and API immigrant counterparts.

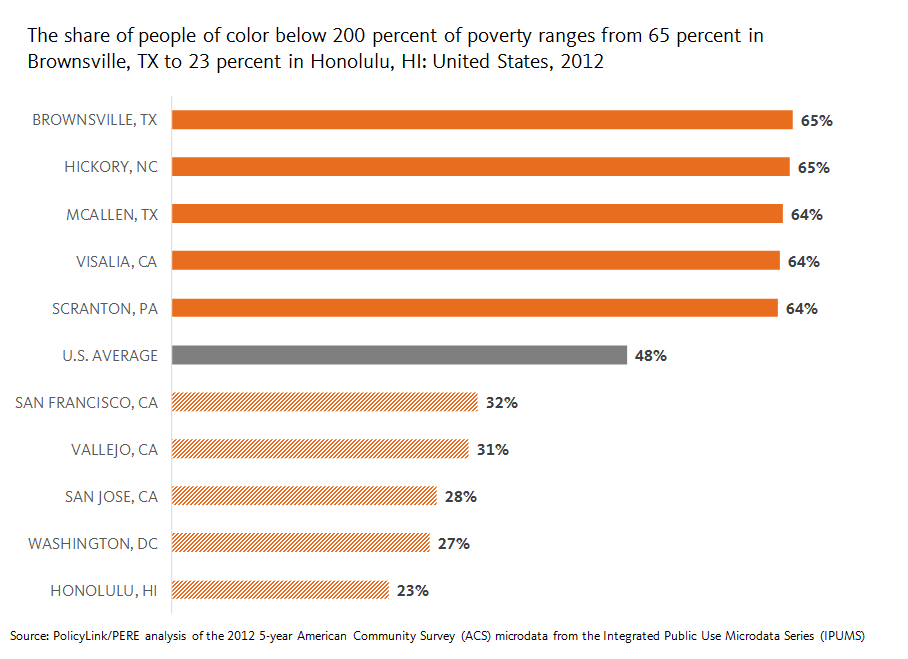

Latino immigrants made up 3 percent of the total U.S. population in 1990, a figure that doubled to 6 percent by 2012. Latino immigrants represent not only the largest share of immigrants in the U.S., but also the fastest growing. The API immigrant community is the second fastest growing and represent 3 percent of the total U.S. population as of 2012. White immigration has more or less stayed stagnant at 3 percent between 1990 and 2012. Finally, Black immigrants make up the smallest share of the total U.S. population at 1 percent, and are not growing as fast as their Latino and API immigrant counterparts. Despite their numbers, Latino immigrants face some of the largest barriers to inclusion. For example, they have the lowest median wage at less than $13/hour, which is $5/hour less than U.S.-born Latinos and half the median wage of White immigrants. Furthermore, 57 percent of Latino immigrants are living under 200 percent of poverty, and 25 percent are working poor.

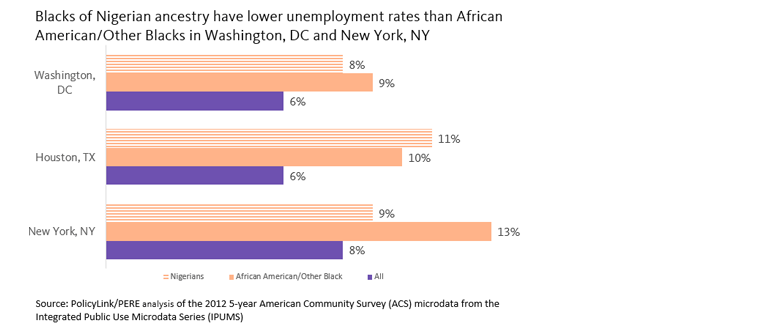

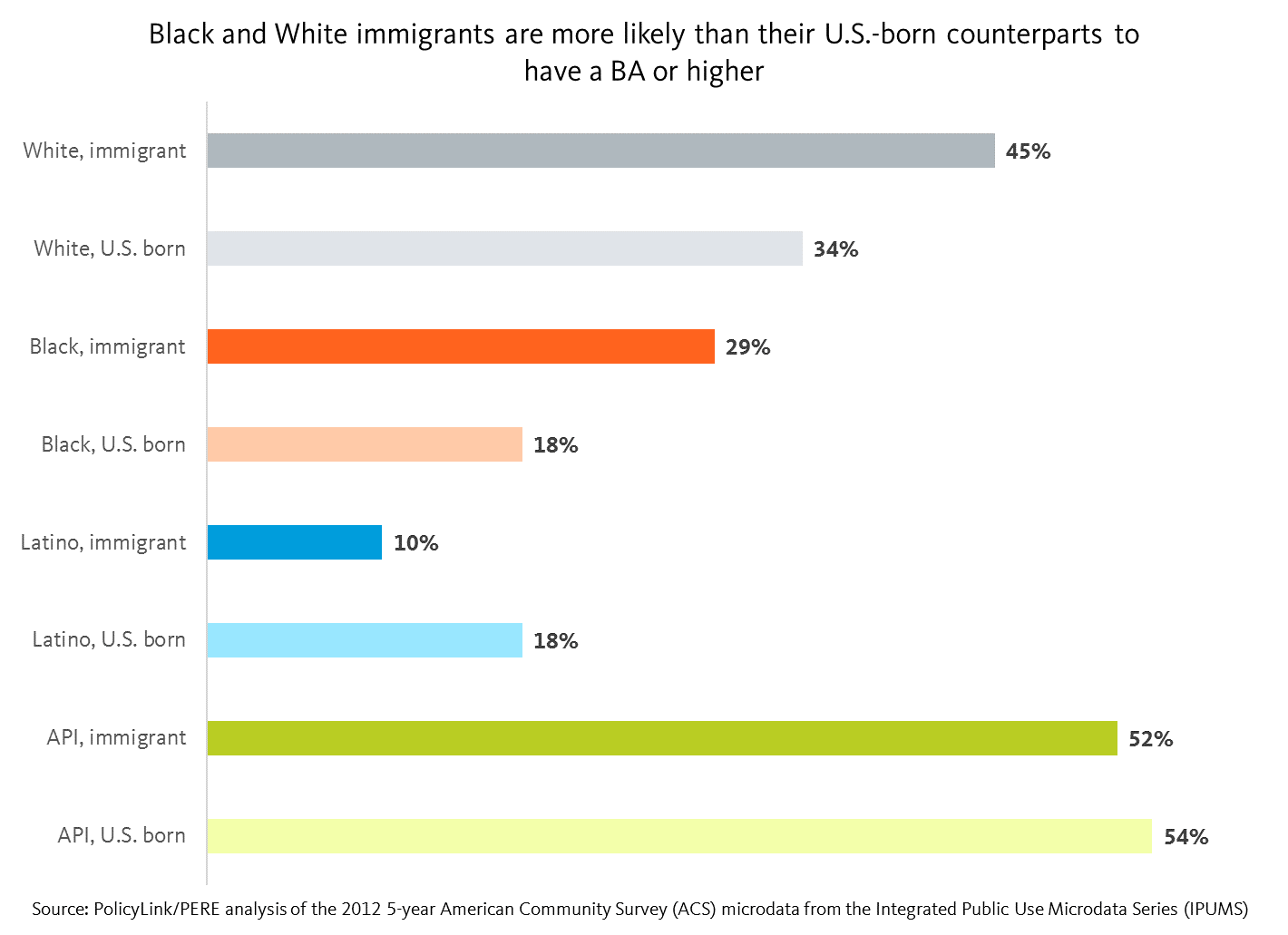

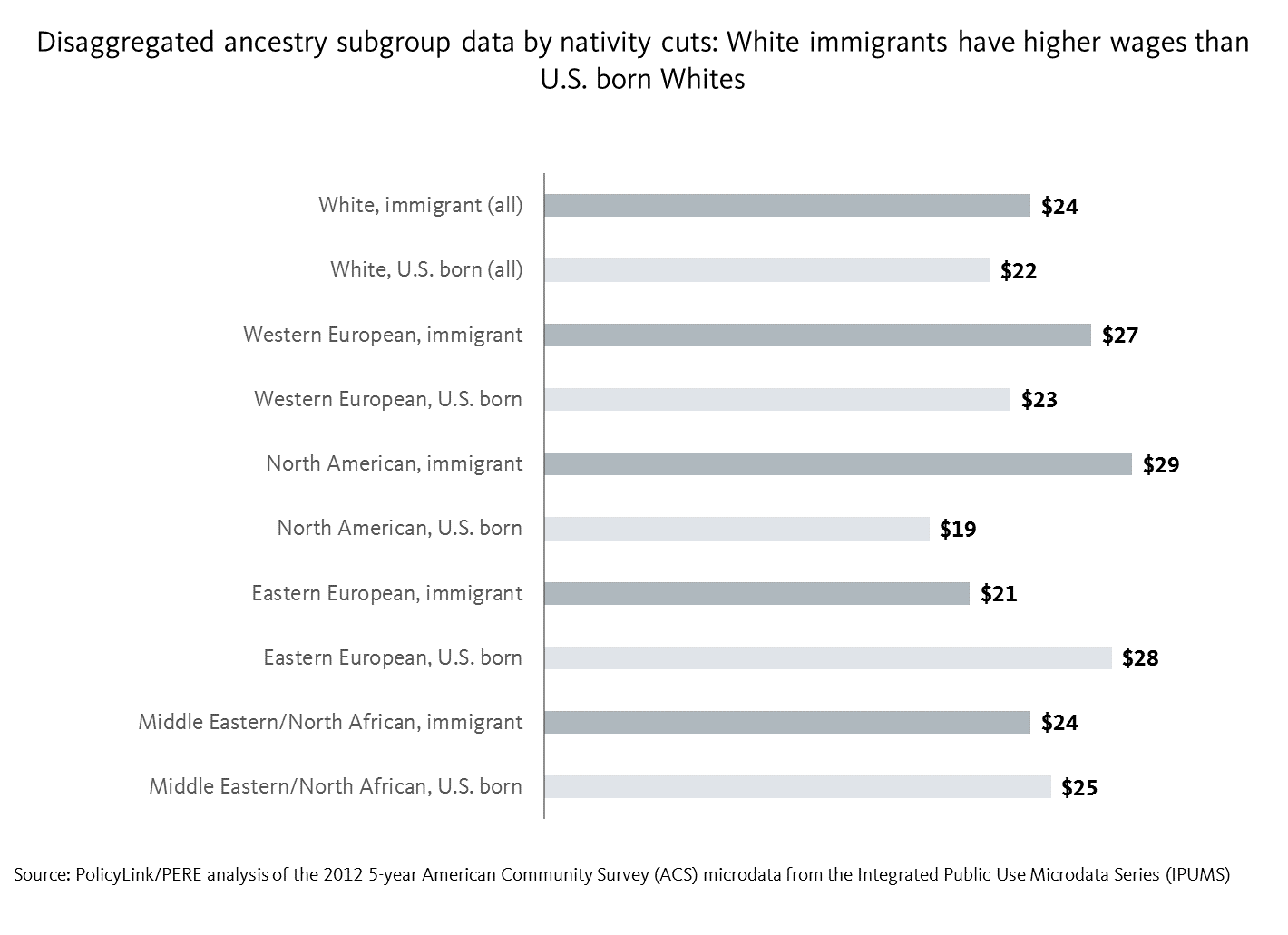

Despite their numbers, Latino immigrants face some of the largest barriers to inclusion. For example, they have the lowest median wage at less than $13/hour, which is $5/hour less than U.S.-born Latinos and half the median wage of White immigrants. Furthermore, 57 percent of Latino immigrants are living under 200 percent of poverty, and 25 percent are working poor. We can do a deeper with-in group analysis by looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by the nativity cuts. For instance, using median wage as an example, immigrant Whites as a whole earn more than U.S. born Whites. Looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by nativity cuts reveals the following: immigrant Whites of Western European and North American ancestry reported lower median wages than their U.S. born counterparts, but immigrant Whites of Eastern European ancestry reported higher median wages than their U.S. born counterparts. On the other hand, immigrant and U.S. born Whites of Middle Eastern/North African ancestry reported the narrowest gap with respect to the disparity in their reported median wages.

We can do a deeper with-in group analysis by looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by the nativity cuts. For instance, using median wage as an example, immigrant Whites as a whole earn more than U.S. born Whites. Looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by nativity cuts reveals the following: immigrant Whites of Western European and North American ancestry reported lower median wages than their U.S. born counterparts, but immigrant Whites of Eastern European ancestry reported higher median wages than their U.S. born counterparts. On the other hand, immigrant and U.S. born Whites of Middle Eastern/North African ancestry reported the narrowest gap with respect to the disparity in their reported median wages. Studies show the significant economic contributions of Latino immigrants

Studies show the significant economic contributions of Latino immigrants Regions in Tennessee and North Carolina have the highest rates of Latino working poverty

Regions in Tennessee and North Carolina have the highest rates of Latino working poverty