Getting to Equitable Growth in the Heartland Region

Nationally, the Omaha-Council Bluffs metro—locally dubbed the Heartland region—stands out for its admirably low unemployment rate. As of September 2014, only 3.6 percent of the region’s residents who are in the labor force were unemployed, compared with 5.7 percent nationally. That means the region is at full employment, if you measure it based on Dean Baker and Jared Bernstein’s standard of 4 percent.

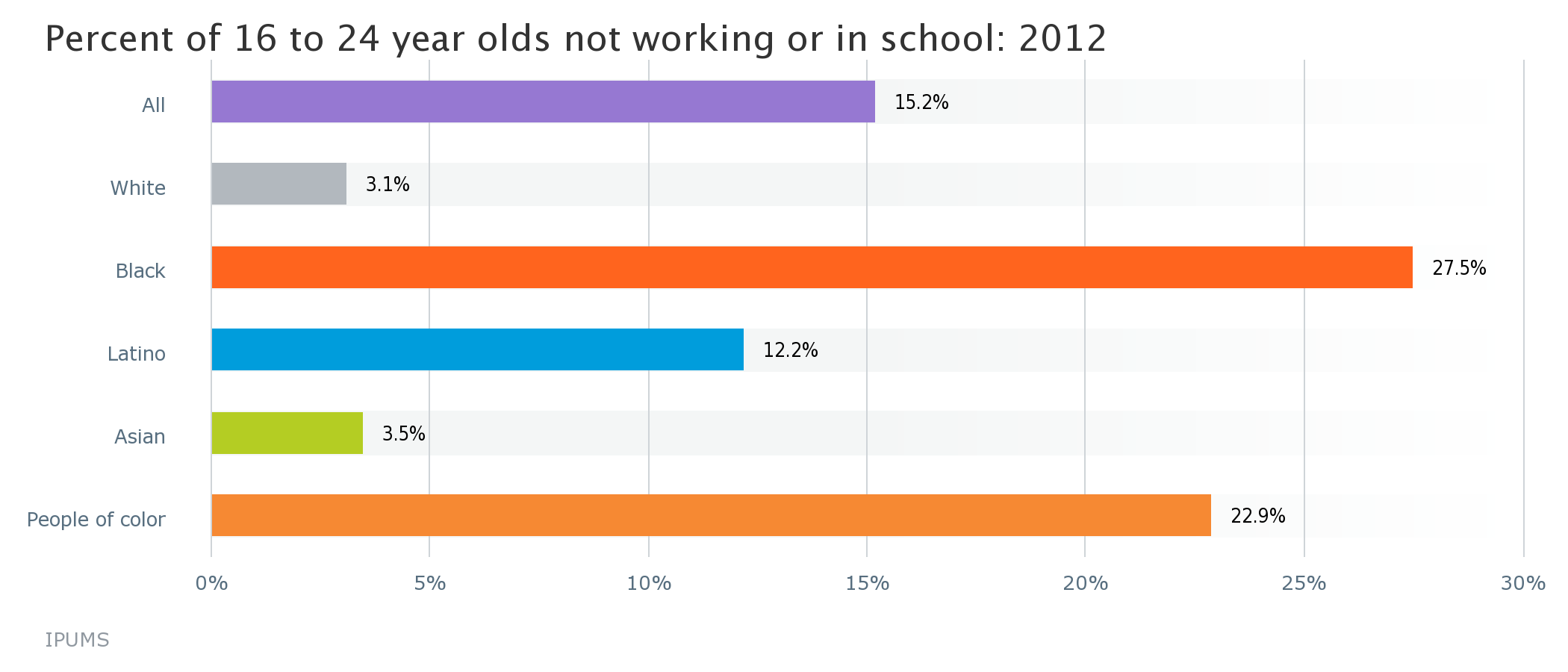

But as is often the case, this broadbrush statistic masks quite a bit. Not everyone is thriving in the Heartland. The unemployment rate for African Americans is closer to 12 percent: three times the average. While communities of color are driving the region’s growth, more and more Latinos, African Americans, and Native Americans cannot make ends meet, even if they are working. And the region has not escaped the challenge of flat wages, either: when you account for inflation, most workers haven’t gotten a raise in the past two decades. (Hopefully Nebraska’s recent minimum wage hike will help budge that statistic.)

This afternoon, community leaders are gathering in Omaha to talk about these trends and why they matter not only for those who are being left behind now, but for the entire region’s economic future.

As a part of the Heartland 2050 process to plan for how the region can double in size by 2050 while increasing equity and resilience, PolicyLink and PERE partnered with the Metropolitan Area Planning Agency and many local organizations to develop a report that lays out the trends and presents strategies for equitable growth.

Released today at a pre-event to Voices for Children in Nebraska’s “Race Matters” conference, the Equitable Growth Profile of the Omaha-Council Bluffs Region illustrates the region’s changing demographics, shows how different groups are faring in the regional economy, and describes what can be done to reduce inequality and steer the region toward equitable growth. You can access the full profile and the summary (which includes the recommended strategies) here.

Here are a few of the trends highlighted in the report:

The region is experiencing a major demographic shift. Between 1980 and 2010, its people-of-color population doubled from 10 to 21 percent. Communities of color will continue to drive growth in the coming decades, growing to 39 percent of the population by 2040.

Credit: Racial/ethnic composition/National Equity Atlas

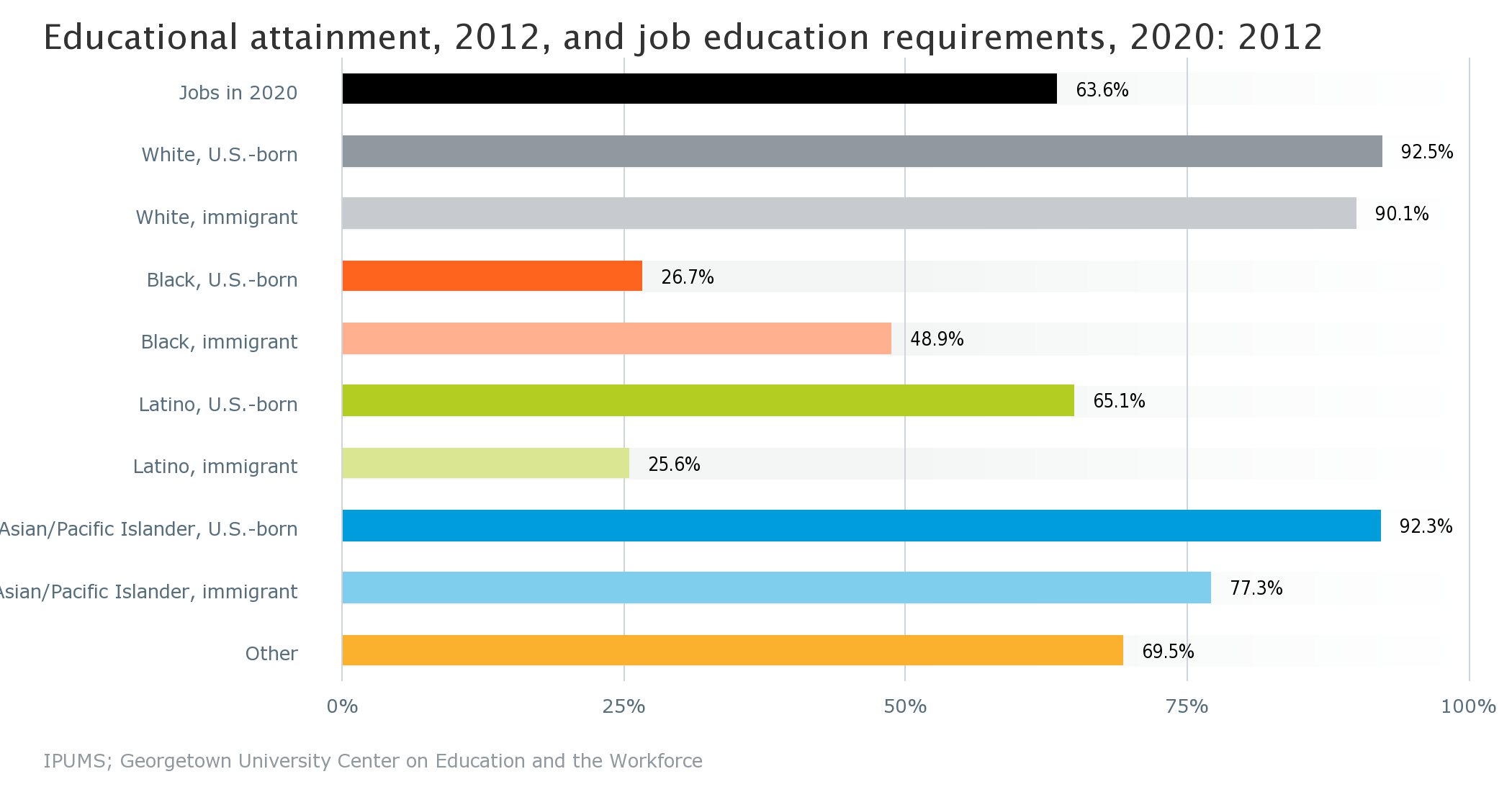

Omaha-Council Bluff's African Americans face disproportionately high rates of unemployment at every level of education.

Credit: Unemployment rate by race/ethnicity and education/National Equity Atlas

Working poverty, defined as working full-time with an income less than 1.5 times the poverty level, is on the rise regionally and is particularly high for Latinos and African Americans.

Credit: Actual GDP and estimated GDP without racial gaps in income/National Equity Atlas