State of Waiting: California’s Rental Assistance Program One Month Before Expiration

Our analysis of program data reveals that fewer than one in six applicants have received assistance thus far, while hundreds of thousands are still waiting, signaling the urgent need for policy fixes to deliver on the program’s promise and keep renters in their homes.

By Sarah Treuhaft, Alex Ramiller, Selena Tan, and Madeline Howard*

Already shouldering some of the worst housing affordability challenges in the nation, California’s low-income renters, predominantly people of color facing the additional burdens of systemic racism, were pummeled by the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic fallout. They disproportionately fell ill and lost family members to the disease, and many lost their jobs or suffered financially from reduced hours and incomes. School closures and a childcare shortage forced many working parents, especially women, to stay home and forego wages. And while California’s renters made tremendous sacrifices to keep current on rent — often incurring large debts to friends, family, and predatory lenders — many ended up falling behind. At the beginning of January 2022, 721,000 renter households in California owed their landlords an estimated $3.3 billion in back rent.

California’s Emergency Rental Assistance Program (ERAP) offers a pathway to clear rent debt that has accrued for low-income tenants impacted by the pandemic. After tremendous advocacy, Congress established a rental assistance program in December of 2020 — nine months into the pandemic — which has provided the state of California with $5.2 billion to operate emergency rental assistance programs. These resources are crucial to prevent evictions, displacement, and homelessness, and to ensure that smaller landlords can make their mortgage payments and stay in business.

These programs have been a lifeline for struggling renters who are able to access them, but they have been riddled with challenges. Many renters vulnerable to eviction have struggled to complete complex applications. Those who do make it through the application process may wait months for their application to be reviewed. And those whose applications are approved face another lag time before they are actually paid. At every stage of the process, the very people and families the program intends to serve and protect are living with the stress of potential eviction, enduring landlord harassment, and losing their homes.

While most of California’s eviction protections expired in October 2021, limited protections remain for eligible renters who apply for rental assistance. However, these protections are expiring on March 31. This means that the hundreds of thousands of families still waiting for assistance will be at imminent risk of eviction unless California policymakers extend these protections. At the same time, the California Department of Housing and Community Development just announced that the program is scheduled to close on March 31, so renters who are eligible for relief but have not yet been able to apply to the program will have no option to do so.

This brief, produced by the National Equity Atlas in partnership with Housing NOW! and Western Center on Law & Poverty, examines the performance of California’s statewide rental assistance program since its launch. The state program covers about 63 percent of the state’s population; the other 37 percent of California residents live in the 25 cities and counties that opted to administer their own programs. Our analysis is based on a dataset tracking all rental assistance applications submitted by renters to the program through February 23, 2022, which we obtained through a Public Records Act request. It includes anonymized individual case data with applicant demographics (race/ethnicity, income, and language of application), zip code, amount of rent and utilities requested and paid, and landlord participation in the application. It also includes detailed case status categories including “Application Complete: Pending Payment,” which is assigned to households that have been approved for payment but have not actually received funds and are still waiting for assistance.[1] We used the 2015–2019 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample to summarize rent burden, racial/ethnic demographics, and primary language, and Census Household Pulse Survey Data on rent debt to compare program applicants and beneficiaries to the likely population of renters in need of assistance.

Our key findings include the following:

- Only 16 percent of renters who have applied to the program have received assistance, either directly or through a payment to their landlord. Nearly half a million renters have submitted rental assistance requests but just 75,773 households have received their payments.

- The majority of applicants are still waiting for their applications to be reviewed. Fifty-nine percent of applicants (289,020 households) are still awaiting a decision on their applications. Among those whose applications have been initially approved, the typical wait time for a response was three months (a median of 104 days).

- Most renters whose applications have been approved are still waiting to be paid. As of February 23, 2022, 180,280 renter households have had their applications approved, but 104,507 of them (58 percent) have not yet received assistance. The median wait time between submitting an application and receiving payment is 135 days, indicating that it takes about a month for applicants to be paid even after approval.

- The speed with which rental assistance is being distributed is improving over time but remains painfully slow. Households that applied for aid in March 2021 typically waited 181 days to receive aid payments, and households that applied in October 2021 typically waited 119 days.

- Most renters who received assistance have requested additional support. Among renter households who have received rental assistance, 90 percent of them (69,336 households) have reapplied to the program for additional support.

- Renters whose primary language is not English appear to be underrepresented in the program. About half (51 percent) of California’s severely cost-burdened renter households speak a language other than English at home, yet 88 percent of rental assistance applicants indicated that their primary language was English.

- Long-term policy solutions, funding, and infrastructure are needed to support California's economically vulnerable renters. With 8,200 new applications submitted every week and 90 percent of rental assistance recipients requesting additional support, tenants’ ongoing need for financial relief due to pandemic-related economic hardship, and the number of indebted renters not yet reached by the program, the need for rental assistance will continue beyond March 31, 2022 (when the program is set to expire).

Our review of the program data reveals the need for urgent policy solutions to fulfill the promise of the state’s rental assistance program, eliminating pandemic-related rent debt for all low-income renters and ensuring that they can stay in their homes. For an equitable recovery, California policymakers need to extend statewide eviction protections without preempting local ones, streamline the application and approval processes and increase equitable access to relief funds, and institute a permanent program to support economically struggling renter households.

Nearly half a million renter households have submitted applications for rental assistance

Since March 15, 2021, when the state began accepting rental assistance applications, nearly half a million renter households (488,094) have applied for relief through the program. Applications peaked in September 2021 just before California’s eviction moratorium ended, with 115,000 renters submitting applications that month. Since January, about 8,200 new renters have submitted applications every week.

Most renters who have applied for assistance are still awaiting a response

Among the half million program applications, the majority — 59 percent, representing 289,020 renter households — are still under review. Four percent (18,794 households) have been explicitly denied assistance, while the remaining 36 percent (180,280 households) have been approved. But just 16 percent of applicants (75,773 households) have actually received assistance.

On average, program applicants wait an average of three months (a median of 104 days) after submitting their applications to receive initial approval. Many renters wait longer: nearly 20 percent of applicants waited more than 150 days to receive initial approval, and 4 percent of applicants waited more than 210 days. [2]

Among renters whose applications have been approved, the majority are waiting to be paid

While 36 percent of program applicants have been approved for relief, less than half of them have received any payment. This means that despite formal approval, 104,507 households are still awaiting assistance.

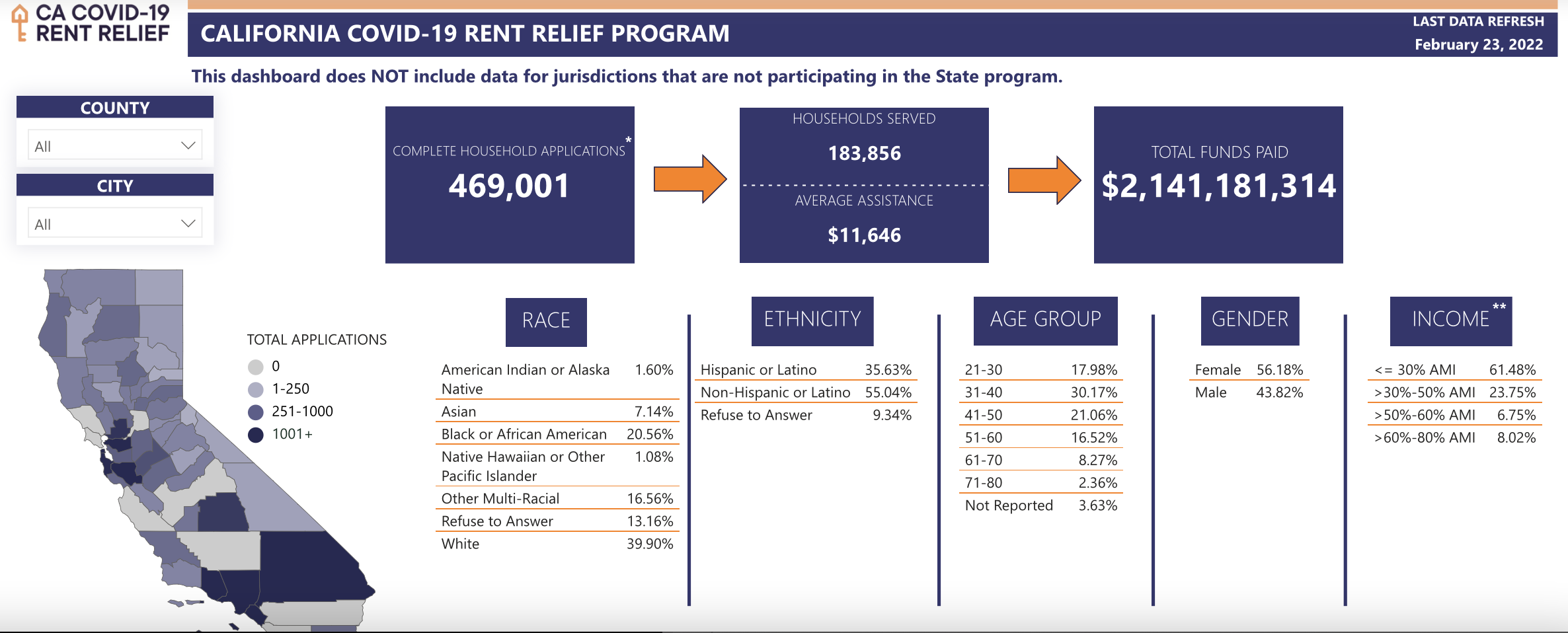

This reality of long delays in relief delivery to renters whose applications have been approved contrasts with the snapshot of program performance provided on the public Housing Is Key data dashboard, which stated that 183,856 households have been “served” as of February 23, 2022.[3]

Although we currently do not have data on the number of days between application approval and receipt of payment, we can examine the number of days between application submission and payment. For renters who have received assistance and have not requested additional support, the median time between submission and payment is 135 days. About 39 percent of recipients have waited more than 150 days to get paid. This implies that the typical renter waits three months just to receive an initial decision on their application, and then another month or more to actually receive aid.

The pace of delivering rental assistance has improved marginally over time. Whereas households that applied for aid in March 2021 waited an average of 181 days to receive aid payments, that figure declined to 119 days by October 2021. The program was delivering assistance most quickly in June and July, before the surge in applications in the fall.

The vast majority of tenants who received rental assistance have requested additional support

About 90 percent of renter households who have actually received funds from the state program (69,336 households) have reapplied to the program for additional funds. Given that applicants who are awaiting review or payment have similar income levels as those who’ve received payment, and most of them are extremely low income, we would expect that these applicants will also require additional assistance after their initial payment.

Renters whose primary language is not English appear to be underrepresented in the applicant pool

Since the launch of California’s rental assistance program, low-income renters who’ve suffered job and income losses due to the pandemic have faced numerous challenges accessing relief. These include technological and language barriers, lack of access for tenants with disabilities, difficulty supplying the necessary documentation of income losses, difficulty communicating with landlords or obtaining documentation from them, and fear of landlord harassment/retaliation and deportation or other immigration-related consequences.

To assess whether California’s rental assistance program is reaching renters with the greatest needs, we compared the racial/ethnic composition of applicants with that of severely cost-burdened renters (those who pay more than 50 percent of their household income for rent and utilities), a population that represents renters at risk of having pandemic-related rent debt. To approximate the statewide program's service area, we excluded from the severely rent-burdened reference group 11 counties and five additional cities that are within areas operating local rental assistance programs. (We also exclude the city of Signal Hill, because it is entirely contained within the Long Beach census geography.)

This analysis reveals that the demographics are similar across both groups, indicating that the statewide program appears to be representative of the renters hardest-hit by the pandemic rent debt crisis. One exception could be Asian and Pacific Islander renters, who might be underrepresented in the applicant pool.

Renters whose primary language is not English, particularly Spanish-speaking renters and Chinese-speaking renters, also appear to be underrepresented in the applicant pool. Among California renters who are extremely cost-burdened, 51 percent speak a language other than English at home, yet 88 percent of program applicants indicated that their primary language is English on the application form. A significant share of the state’s severely cost-burdened renters speak Spanish at home (32 percent), yet only 10 percent of applications were submitted by people who indicated that Spanish is their primary language.

Renters whose primary language is not English, particularly Spanish-speaking renters and Chinese-speaking renters, appear to be underrepresented in the applicant pool. Among California renters who are extremely cost-burdened, 51 percent speak a language other than English at home, yet 88 percent of program applicants indicated that their primary language is English on the application form. A significant share of the state’s extremely cost-burdened renters speak Spanish at home (32 percent), yet only 10 percent of applications were submitted by people who indicated that Spanish is their primary language.

The demographics of program recipients reflect the demographics of the applicant pool

The federal emergency rental assistance program is targeted to low-income renters experiencing negative financial impacts due to the pandemic, and thus is means-tested: applicants need to have incomes below 80 percent of the area median income in order to qualify for assistance. In addition, the state program has prioritized serving tenants who indicate that they are imminently facing eviction, either on their application or via email correspondence. [4] Our analysis shows that the incomes of program applicants and recipients reflect the program’s targeting: well more than half of renters who apply to and are served by the program are extremely low income.

Examining the racial/ethnic composition of applicants compared with those who are approved for and receive payment, we see that the demographics are similar and the program itself appears to be serving applicants equitably by race/ethnicity.

<>

California needs permanent policy solutions, funding, and infrastructure to support economically vulnerable renters

California’s statewide rental assistance program was initially allocated $3.07 billion by the federal government and received an additional $62 million in January when the Treasury began reallocating funds. Approximately $900 million in aid has been delivered to struggling renters and landlords, and another $1.15 billion is in the process of being delivered to applicants whose payments are pending. An additional $4.97 billion has been requested by households with applications still under initial review. That adds up to just over $7 billion in total requests to date, with 8,200 new requests coming in every week and 90 percent of aid recipients requesting additional support. The need continues to grow as we approach the end of the program on March 31.

Recognizing the critical demand for additional funding to ensure all eligible renters who apply in time can receive assistance, California’s legislature passed a bill this month that allocates General Fund resources to state and local rental assistance programs.

This budget allocation fills an urgent need, especially given that many locally administered programs have already exhausted their funds. But it will not be sufficient to protect and stabilize all vulnerable households still reeling from the economic impacts of the pandemic. The program’s expiration date of March 31, 2022 is an artificial and arbitrary endpoint, as the need for rent relief is ongoing and still extensive, and many eligible renters have not yet applied. Despite the desire to return to normal, many renters continue to face Covid-related economic hardships. Recognizing the pandemic is not over, the state of New York and Los Angeles County have extended eviction protections through the end of 2022, and California should follow suit.

Urgent policy fixes are needed to realize the promise of California’s rental assistance program

When California’s eviction protections expire on March 31, 2022, tenants eligible for assistance who are still waiting to receive payment can face eviction in court — and many will. With application processing times lasting four months and beyond, tens of thousands of tenants are likely to still be waiting when these protections expire. If the legislature does not extend eviction protections, many Covid-impacted renters may lose their homes because of the application backlog, exposing families and communities to the cascading harms of housing precarity and homelessness. Even with temporary protections in place, every day of delay leaves families more vulnerable to eviction and unable to make financial plans.

Some local governments, including Alameda County, Los Angeles County, Fresno, San Francisco, and Stockton have passed their own eviction protections for tenants who could not pay rent because of the economic impacts of Covid-19. Extending statewide eviction protections while allowing local governments the flexibility to meet the needs of their communities is the most effective way to stabilize vulnerable renters and keep them in their homes while assistance is distributed.

The pandemic has deepened the harms of structural racism on communities of color, who have suffered disproportionate deaths, job losses, and housing instability. Continuing to conduct outreach to underrepresented communities of color is imperative to ensure that rental assistance dollars do not further exacerbate the racialized harms of the Covid-19 pandemic.

For California’s rental assistance program to be effective, California’s policymakers need to:

- Protect people from eviction by extending the state’s current eviction protections;

- Ensure local jurisdictions can enact and strengthen eviction protections;

- Streamline the screening and payment process for rental assistance;

- Promote equity by increasing outreach to underrepresented renters; and

- Fund the rental assistance program to ensure low-income tenants receive ongoing support.

* Madeline Howard is is a senior attorney at Western Center on Law & Poverty.

Correction (March 7, 2022): The March 3, 2022 version of this report included a data error relating to the racial/ethnic composition of severely rent-burdened households in California due to incorrect weighting of the sample data. This incorrect data suggested that Latinx households were underrepresented in the statewide rental assistance program. We have corrected the data and we no longer find any underrepresentation of Latinx households, so we have updated the analysis of the data to reflect this (positive) new finding.

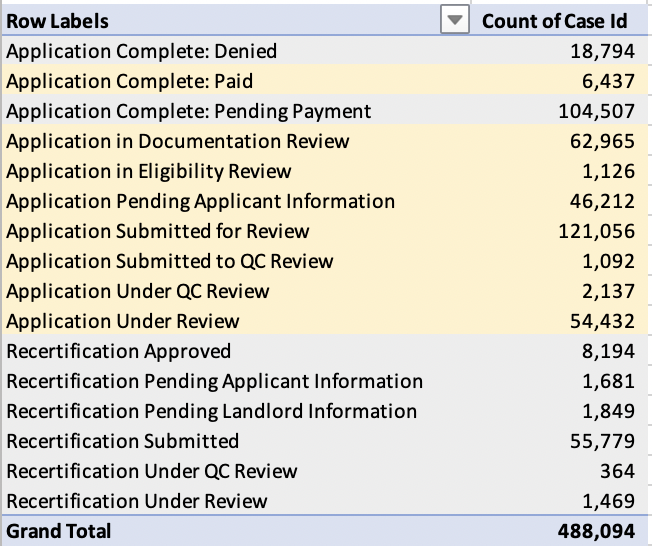

[1] The table below, provided directly from the Department of Housing and Community Development in response to a Public Records Act request, shows the number of cases across the 16 case status categories provided in the dataset. “Approved” applications in this analysis include all applications in the categories "Application Complete: Paid," “Application Complete: Pending Payment," and all Recertification categories. “Application Complete: Pending Payment” means the application is approved for payment and a request for payment has been made, but the applicant has not actually received funds. “Recertification” means that applicants have received payment and have requested additional assistance. Applications that are categorized as “Application Complete: Paid” and those that fall under any of the recertification categories represent tenants that have actually received assistance.

Detailed case categories

[2] This median wait time is for renters who have received initial approval but have not yet been paid.

[3] The slight discrepancy of the number served on the public dashboard and the total paid renter households reported here is due to the timing of the database pull and continual program activity.

[4] This is based on two sources of information: 1) a positive response to the question, “Has your landlord issued a Notice to Pay, an Eviction Notice, filed an Unlawful Detainer against you due to unpaid rent, or indicated they will be seeking to evict you?” on the rental assistance application; and 2) applicants who send information about a pending eviction to the evictionprotections@ca-rentrelief.com email box including documentation from the landlord or legal documents related to an unlawful detainer (the final stage of the eviction process).