Uber and Lyft promised drivers good pay, benefits, and flexibility with California’s Prop 22.

What drivers got were poverty wages.

Today, rideshare drivers have to work longer than ever, up against the companies’ cryptic algorithms—and make just $6.20 net per hour.

In California, where the majority of drivers are people of color and immigrants, Prop 22 makes statewide gaps in earnings and protections between white workers and workers of color even worse.

Under Prop 22, Uber and Lyft make workers shoulder all the costs and risks, while giving them none of the benefits

That’s because they misclassify drivers as independent contractors to get out of guaranteeing workers a minimum wage or providing benefits like health insurance and paid sick leave. And Uber and Lyft are working hard to keep it that way. In 2020, they drafted and campaigned for their own ballot initiative in California, Prop 22, after the state passed a law saying rideshare companies would have to ensure basic pay and benefits for drivers. Uber and Lyft spent $224 million promoting Prop 22, promising drivers that it would give them flexibility, more pay, and benefits—and legalize their classification as independent contractors. Prop 22 passed in 2020—and the result has been just the opposite.

With Prop 22 in place, Uber and Lyft have changed their algorithms to take more control away from drivers, causing them to have to work longer than ever to make ends meet. When you factor in all the hidden costs offloaded onto drivers, our first-of-its-kind study based on real driver data shows their average net earnings are just $6.20 per hour. If rideshare companies were forced to respect drivers’ labor rights, drivers in California would earn up to three times more per hour.

While drivers make poverty wages, Uber & Lyft capitalize off workers struggling to make ends meet

“The biggest struggle is the day-to-day. Having food on the table. Being able to pay rent. And the worst part is when you have something that is small to other people, like a parking ticket or speeding ticket that can derail you for months, and you go into debt.” —Mae Cee, Uber & Lyft Driver, San Francisco

Mae Cee has been an Uber and Lyft driver in the Bay Area for eight years. During Covid, she dropped down to part-time, realizing that she was losing money driving for the apps full-time while renting a car. When you add up the taxes workers have to pay, plus the benefits they are denied like unemployment insurance, workers’ comp, paid time off and sick time—drivers like Mae Cee can barely make ends meet.

Uber and Lyft promised drivers they’d make more than minimum wage—but they’re earning as little as $4.10 per hour

Imagine if you worked at a drive-through, and your boss clocked you in the moment a customer pulled up to order, and then out again when the customer drove away. After eight hours, you might make only half a day’s wages. On a busy day, you could make more—but no guarantees. Under California’s Prop 22, this is what Uber and Lyft do to drivers by misclassifying them as independent contractors.

During their campaign, Uber and Lyft guaranteed drivers they would make at least 120 percent of California’s $15 minimum wage under Prop 22. But, the only time they count as “working” is the time between when they accept a ride and when the customer leaves the car, not the waiting time. The apps also have total control over how many and which rides drivers are offered. The result is drivers spend a lot of time waiting—in this study, over a quarter of their total work time. In reality, when you subtract the costs of unpaid waiting time and all the benefits drivers are denied, the wage floor under Prop 22 is just $4.10 per hour.

Uber and Lyft promised healthcare benefits, but very few can access them

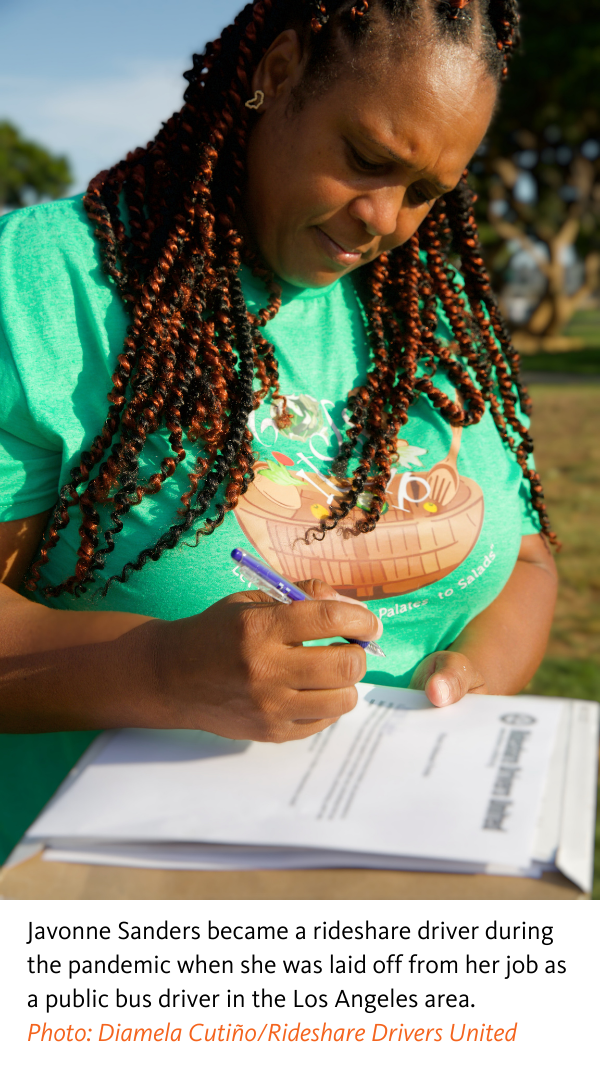

“I just take vitamins and be cautious of who is out there.” —Javonne, a rideshare driver based in the Los Angeles area who doesn't have health insurance

Javonne became a rideshare driver during the pandemic when she was laid off from her job as a public bus driver for the City of Gardena near Los Angeles, losing her health insurance. To manage, she says she tries to limit her health risks, sprays down her car, and keeps the windows down with passengers in the car to avoid Covid. Eighty-nine percent of the drivers in this study are uninsured or on Medi-Cal, which is for people below 138 percent of the poverty line. That’s because the healthcare benefits Uber and Lyft promoted in their Prop 22 campaign are not accessible to most. Drivers can qualify for a stipend to cover 82 percent of their health insurance premium, but only if they average 25 hours a week of actively driving passengers—not total actual working time. Yvette, a driver in Los Angeles, was just 13 minutes short the first time she applied for the stipend, and was denied. Whether or not workers like Yvette hit this threshold is ultimately up to the apps, because they control how many and which rides drivers are offered—so drivers can work 40 to 60 hours a week attempting to reach the 25-hour mark. This setup makes drivers less likely to buy insurance altogether, because there are no guarantees month to month that they will qualify for the stipend, no matter how much time they put in on the road.

While campaigning for Prop 22, Uber introduced flexible app features drivers would like. After Prop 22 passed, it took them away. Now, drivers have less choice over their rides, and they have to work more to earn less.

“Before [Prop 22], I could make three times more. . .Now I have to work 8 to 10 hours a day.” —Serhii, Rideshare Driver, Bay Area

In the leadup to the vote on Prop 22, Uber introduced features that would give drivers more flexibility to choose what rides to take, as well as more opportunities to earn bonuses. After it passed, Uber changed its formula. First, it swapped its pre-set, dependable multiplier feature for a hard-to-achieve bonus.

Javonne, who works 55 hours a week in the Bay Area, said, “It’s hard to get the bonus. Sometimes there isn’t any out there. I get frustrated sitting in traffic on the 405 or 101. Some people have probably mastered it. . .I just want to pay my bills.”

Uber also took away a feature that gave drivers information about a ride offer, like the passenger’s destination and fare, so they could make an informed choice about whether to accept it. Now, drivers must accept rides without any of this information in order to keep getting ride offers.

Serhii said in 2020, he was able to make $1,000 or $1,500 per week by driving a few hours and choosing the rides he would take while he studied at home. Now, he says, “I have to have at least 5 out of 10 [rides accepted] in order to see [that information].” Despite working eight to ten hours a day, he says, “The money I make is really little, and with the gas prices I don’t feel it is worth it.”

Prop 22 worsens the statewide gaps in earnings and protections between workers of color and white workers

J.K. Wong believes he has faced ride cancellations due to anti-Asian discrimination. He says passengers will cancel, and then the app pings him again for the same rider that had rejected him, over and over. Although he knows the passenger will continue to cancel the ride, he feels forced to reaccept rides from the same passenger repeatedly to keep his acceptance rate and access bonuses.

Prop 22 offers no protections for discrimination like the kind J.K. Wong faces—instead, it allows discrimination to become part of the job. In a state where a majority of rideshare drivers are people of color and immigrants, Prop 22 locks in low pay and zero protections, making inequities worse between white workers and workers of color.

With full labor rights, rideshare drivers could earn up to $16.70 per hour—but it will take a fight

Prop 22 gives Uber and Lyft a free pass to pay poverty wages to their drivers and deny them critical rights and protections. Now, these companies are working to pass similar laws in other states. But drivers can fight back to win what they deserve.

With basic labor rights, drivers could make $16.70 per hour in net earnings, including tips.

Join Rideshare Drivers United in the fight for a fair, dignified, and sustainable rideshare industry!

Policymakers nationwide must act to protect rideshare drivers’ rights

Uber and Lyft are attempting to pass Prop 22-like legislation throughout the US—but policymakers can push back by advancing laws that guarantee labor rights and protections for all workers, including rideshare drivers.

- Ensure all workers, including app-based workers, are covered by full labor and employment rights and protections, including a living wage, the right to organize their own unions, and the right to collective bargaining. Such provisions should be included in any labor-related legislative proposals, such as the Protecting the Right to Organize Act, and should impose strict penalties for union-busting efforts. These changes will improve job quality and increase worker power for app-based workers and workers across all sectors.

- End the widespread abuse of independent contractor status to misclassify workers and deny them full labor rights. Workers need legislative action that prevents employers from using misclassification to deny access to minimum wage, health insurance, paid sick leave, family leave, and other key employment rights. In California, this requires the immediate repeal of Prop 22. As this study demonstrates, the promise of Prop 22 to make up for lost employment benefits has failed workers. The federal government should also pass legislation to protect against misclassification. The “ABC test” described in California’s AB5 Bill, and a standard for many states across the country, could serve as a model.

- Require app-based companies to make their algorithms transparent to workers and public agencies to prevent discrimination and other harm to workers. Drivers and public agencies are entitled to know how rides are assigned and other app-based decisions are made (like bonus assignment) to ensure fairness in ride assignment and compensation as well as prevent discriminatory impacts for protected classes of workers. Public agencies should also have regular access to anonymized trip datasets to ensure effective regulation, similar to requirements passed in New York City.

- Increase worker control and autonomy over personal data collected while on the job. Policies should be enacted that give app-based workers more control over how their personal data may be used and grants them access to the data that companies collect from them while they are on the job. Drivers should also have increased access to crucial, real-time data that affects their work, like passenger destinations and fares.