Regional Snapshot: Indigenous Residents in the Albuquerque, New Mexico Metropolitan Area

Note: This article is not intended to be a comprehensive survey or study of Indigenous residents in the Albuquerque region. Rather, these regional snapshots provide a few examples of recent policy changes, Indigenous-led housing and land campaigns, and/or population changes relevant to our overall analysis. Indigenous populations are diverse in makeup, and different regions of the US have different local histories of Indigenous colonization, migration, and/or political representation. Focusing on four individual regions helps to illustrate some of these regional differences and the unique character of local Indigenous housing politics.

We also encourage you to learn more about Albuquerque’s Indigenous communities from the 19 Pueblos, Navajo Nation, and Jicarilla Apache Nation, all of which have reservation lands in northern New Mexico.

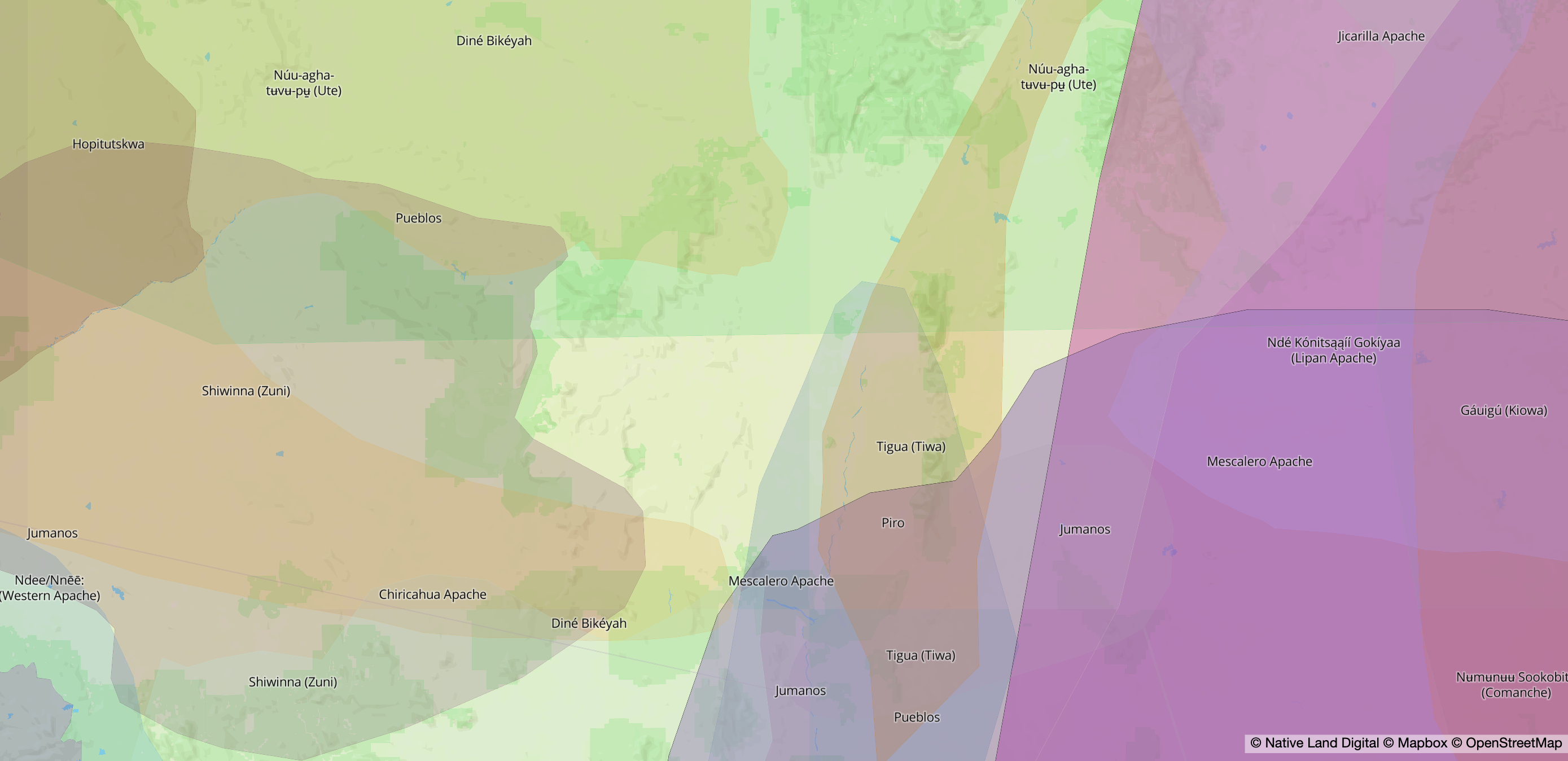

Territorial map of nations and tribes indigenous to the Albuquerque metropolitan area. Source: Native Land Digital. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

The Albuquerque, New Mexico metropolitan area (Bernalillo, Sandoval, Torrance, and Valencia counties) has been fundamentally shaped by the region’s original inhabitants. The state’s 19 federally recognized Pueblos are modern-day versions of the independent city-states that Spanish explorers first encountered in the 1500s, and the metropolitan area also includes parts of Apache and Navajo tribal territory. Each Pueblo continues to maintain its own tribal governance structure, including elected and appointed officials. Albuquerque and northern New Mexico are home to rich legacies of Indigenous survival and resistance. Most famously, during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, an alliance of local Pueblo people successfully expelled Spanish settlers from the region for over a decade.

Indigenous residents continue to comprise a sizable portion of the regional population. As of 2022, the Albuquerque metro area is home to about 82,700 people who identify as Indigenous; this 9 percent Indigenous population rate ranks fourth-highest in the US, behind only Honolulu, Oklahoma City, and Tulsa. However, there was not a single neighborhood in the region in either 2016 or 2022 with a median market rent affordable for a median income Indigenous renter household. The region’s median hourly wages for Indigenous workers ($15.09) are the 12th-lowest among the 76 US metros under analysis. Thus, thousands of Indigenous renters in the region struggle with housing security and affordability.

The Albuquerque metro area is a salient example of the frictions between political recognition and community well-being. The region’s Indigenous community, rooted in the many reservations throughout Northern New Mexico, is foundational to the region’s culture, and local government includes spaces for Indigenous community representation. However, the regional importance of Indigenous history, culture, and politics has not been reflected in housing policies or development decisions that support Indigenous renters specifically, as well as all low-income residents in general. The following are a few examples of local advocacy efforts.

Indigenous Representation and Resistance

While Indigenous communities in many US metros struggle for recognition from local governments, Albuquerque’s city government has multiple avenues for Indigenous representation. The city operates a permanent Office of Native American Affairs and has hosted a Commission on American Indian and Alaska Native Affairs since 1994, which currently has 14 seats.

The city also sponsors ad hoc projects to address Native American community needs, such as a Native American housing survey launched in 2024. Housing precarity and houselessness have been a persistent issue for the city’s Indigenous population, as many residents leave the reservations in search of economic and educational opportunities but then struggle to find affordable housing and livable wages in urban Albuquerque. In 2014, the murder of two houseless Navajo men by a group of teenagers prompted the city to establish a Native American Homelessness Task Force, which produced a thorough list of recommendations and prompted the expansion of the permanent commission to include more members. However, Indigenous residents continue to make up an outsized share of people experiencing houselessness. Per the 2024 Point In Time Count, Indigenous residents comprise 16 percent of the unhoused population, while making up just 5 percent of the overall population.1

The endurance of Native American poverty and anti-Indigenous violence has also prompted other Indigenous residents to take more oppositional grassroots approaches outside of formal governmental channels. In the mid-2010s, local Indigenous activists and students formed the Red Nation, a collective that started by conducting grassroots research on anti-Indigenous violence in the region. Since then, Red Nation has expanded its activities to include campus organizing, peer education through digital media, and protests against local statues commemorating Spanish conquistadors. In its platform, Red Nation calls for “free housing, food, clean drinking water, education, mobility, employment, and healthcare” for all, as well as the return of Indigenous lands to their original caretakers.

The Challenges of Data Advocacy

While Albuquerque has a relatively large Indigenous population with significant cultural influence throughout the region and representation in local government, current data infrastructures are not robust enough to fully understand and address the needs of local Indigenous communities. Because Native American tribes have been a constant presence in Albuquerque since the era of Spanish conquest, many New Mexico residents can claim some degree of Native American ancestry, including many people who are not formal citizens of Indigenous nations. However, the American Community Survey and Decennial Census only capture race, not tribal citizenship, which limits the use of these datasets in highlighting the particular circumstances that tribal citizens face, whether while living on reservation lands or in metropolitan areas. This data gap is especially noticeable in New Mexico, which is home to 23 federally recognized tribes and people from many other Indigenous nations.

However, as local advocates note, getting more detailed data may not just be a matter of having the capacity to collect it. Some tribal governments adopt a more protectionist stance, and some Indigenous residents may hesitate to be enumerated in data projects, given a legacy of social scientists targeting local nations and peoples as objects of study.2 Successful data and research projects in the state, like the New Mexico KIDS COUNT program, rely on formal relationships with tribal governments. A more comprehensive data equity strategy will require a ground-sourced approach: centering Indigenous residents and researchers as decision makers and utilizing the insights of Indigenous community members to refine population-wide data tools like the ACS.

Local Land Back and Rematriation Movements

In recent years, Pueblo leaders and other tribal organizations have led Land Back campaigns, which aim to receive or purchase plots of land from public or private entities and restore Native cultural, political, and economic stewardship of the land. Recent local rematriation efforts have mostly focused on wilderness areas on the outskirts of the metropolitan area rather than urban spaces:

- In 2016, the Santa Ana Pueblo in Sandoval County spent over $30 million to acquire Alamo Ranch, a working cattle ranch and former US military training site over 60,000 acres in size, that was part of the Pueblo’s ancestral lands. In 2024, the Pueblo partnered with the US Department of the Interior to sign the lands into trust, thereby preventing any future sales and retaining the land for the Pueblo in perpetuity. Pueblo leaders intend to preserve the land, reclaiming its name of Tamaya Kwii Kee Nee Puu, for its natural flora and fauna, and do not plan to develop it further.

- Since 2018, US representatives from New Mexico (first Michelle Lujan Grisham, then Debra Haaland, and then Melanie Stansbury and Teresa Leger Fernandez) have introduced congressional bills to restore Indigenous sovereignty of the Ball Ranch area to the San Felipe Pueblo in Sandoval County. In 1987, the federal Bureau of Land Management designated nearly 7,200 acres of land within the San Felipe Pueblo as an Area of Critical Environmental Concern, assuming control of the area for conservation and preservation efforts. If passed, the bill would direct the Department of the Interior to return stewardship of the land to the Pueblo, under the understanding that the original inhabitants are the most knowledgeable and capable of preserving the land’s ecosystem.