Regional Snapshot: Indigenous Residents in the Los Angeles, California Metropolitan Area

Note: This article is not intended to be a comprehensive survey or study of Indigenous residents in the Los Angeles region. Rather, these regional snapshots provide a few examples of recent policy changes, Indigenous-led housing and land campaigns, and/or population changes relevant to our overall analysis. Indigenous populations are diverse in makeup, and different regions of the US have different local histories of Indigenous colonization, migration, and political representation. Focusing on four individual regions helps to illustrate some of these regional differences and the unique character of local Indigenous housing politics.

We also encourage you to learn more about the past and present of Los Angeles’s local Indigenous communities from the experiences and insights of tribal members living in the region.

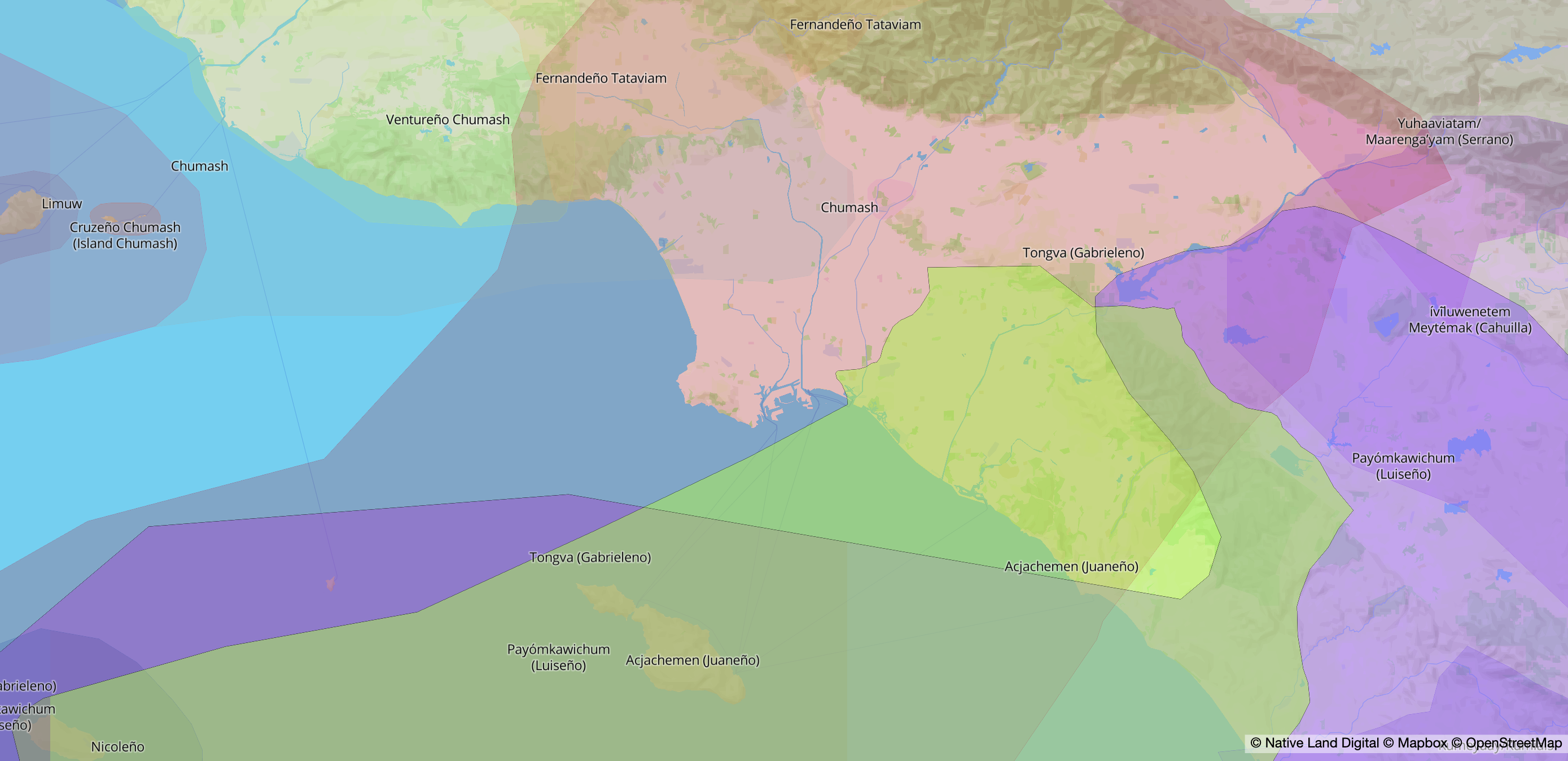

Territorial map of nations and tribes indigenous to the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Source: Native Land Digital. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

The Los Angeles metropolitan area (Los Angeles and Orange counties) is an epicenter for Indigenous migrants, from other parts of the US and from other parts of the Americas. Los Angeles is home to the largest Indigenous population in the US, with over 360,000 residents identifying as Indigenous as of 2022. Nearly two-thirds (64 percent) of Indigenous residents also identify as Latinx. The region is also home to the largest Native Hawaiian population outside of Hawaiʻi, with over 32,000 residents in 2022. However, the metro area is one of the least affordable in the US for its Indigenous residents. In 2022, none of the region’s 348 zip codes offered a median market rent that was affordable for median-income Indigenous renters. In 21 neighborhoods, the median market rent actually exceeded the regional monthly income for the median Indigenous rental household.

Because Los Angeles is home to many Indigenous residents from across the Americas, Indigenous community issues take multiple forms, and Indigenous-led advocacy is similarly diverse. The region’s original inhabitants are engaged in campaigns around federal tribal recognition and land sovereignty, while other Indigenous migrant communities organize around language access and other cultural and social supports. A few examples follow.

Tongva Struggles for Federal Recognition

The Tongva people, or Gabrielinos,1 are the original inhabitants of the Greater Los Angeles Basin, with a civilization (known as Tovaangar) reaching across much of current-day Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside counties. Tovaangar was thrice colonized: first under the Spanish crown, starting with the settlement of Mission San Gabriel in 1771; then under the period of Mexican independence, from 1821 to 1848; and has been under US jurisdiction ever since following the end of the Mexican-American War. Tongva residents were forced into enslavement as laborers in the mission system, rendered refugees upon dispossession of their tribal lands, and subject to famine and disease. When California became a state within the United States, all of the treaties that had been forged previously between tribal nations and Mexican settlers were left unratified by the US government.

The Los Angeles region is still home to a few thousand Tongva members, despite the death and displacement of the majority of the region’s original inhabitants. In 1994, the State of California recognized the Tongva as “the aboriginal tribe of the Los Angeles Basin.” However, none of the multiple current tribal organizations claiming representation of the Tongva has achieved federal tribal recognition, leaving local Tongva communities without access to key federal tribal funds or a land base. Tongva leaders contend that the region’s lucrative real estate market and high property values deterred federal recognition, as the federal government was unwilling to make land purchases in the region to establish a Tongva reservation. The struggle for federal recognition continues, with some support from elected officials. In 2023, US Representative Sydney Kamlager-Dove, who represents parts of South Los Angeles, introduced HR 6859, a congressional bill that would establish the federal recognition of the Gabrielino/Tongva Tribe (one of the four entities claiming Tongva leadership and the group that the state government recognized in 1994). As of the time of writing, the bill is still awaiting discussion in the House Committee on National Resources.

Local Land Back and Rematriation Movements

In recent years, Tongva movements for tribal sovereignty have also included Land Back campaigns, or efforts to receive or purchase plots of land from public or private entities, and restore Native cultural, political, and economic stewardship of the land. These Land Back campaigns have led to a few successful land returns, or rematriations:

- In 2022, the Tongva Taraxat Paxaavxa Conservancy (TTPC) received a private one-acre land donation in Altadena, signifying the first time in centuries that Tongva communities had land rights in the Los Angeles region. The TTPC has plans to establish a community center and affordable housing on the land, now known as Huhuunga (“the place of the bears”).

- Also in 2022, the University of California - Los Angeles entered into a land use agreement with the Gabrielino/Tongva San Gabriel Band of Mission Indians, one of the unrecognized Tongva tribal governments. Under the agreement, tribal citizens steward portions of the UCLA campus with native plant life, including a section of the school’s botanical garden, and will lead community programs in Sage Hill, an undeveloped portion of the campus.

- In 2023, the Gabrielino Shoshone Nation of Southern California (another federally unrecognized tribal government) purchased 12 acres of land in the Monterey Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles, northeast of downtown. The land is now known as the Chief Ya'anna Learning Village and Tuatukar Eco-Cultural Center, and the Gabrielino Shoshone Nation has plans to develop a community center, amphitheater, gardens, and other community amenities on the land. The Gabrielino Shoshone Nation is also affiliated with Anawakalmekak, a local Indigenous-led TK–12 charter school that integrates Native pedagogy and lifeways into the curriculum.

A Region of Indigenous Migrants

Tongva citizens make up a small share of the over 360,000 residents in the Los Angeles metro area who identify as Indigenous. The region is also home to the largest concentration of migrants from Indigenous communities in Latin America and provides an existing network of supportive services and cultural institutions for Indigenous migrants fleeing poverty, natural disasters, and political unrest in their places of birth. According to a report from the USC Equity Research Institute and Comunidades Indigenas en Liderazgo (CIELO), over 36,000 residents in Los Angeles County identified with an Indigenous nation in Mexico or Central America on the 2020 decennial census. However, this figure is likely an undercount, as some migrants speak neither English nor Spanish and may not have been able to complete the census on their own.

As the report indicates, Indigenous migrants from Mexico and Central America are valuable to the region, working in many essential industries at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, and leaving a strong cultural imprint in Los Angeles neighborhoods like Pico-Union and Westlake. However, many Indigenous migrants have also struggled with housing, job, and food insecurity, with conditions further exacerbated since the start of the pandemic. Given the language barriers that many Indigenous migrants face, community-based organizations like CIELO are essential in connecting community members to crucial services, disseminating information, and providing a local support base for newer arrivals.

Beyond Indigenous Latin American immigrants, the Los Angeles region serves as a migrant hub that draws people from all parts of the US, including Indigenous people from many different tribes and nations. Because Los Angeles’s Indigenous population is so ethnically, linguistically, and culturally diverse, housing resources, social supports, and cultural programming for Indigenous residents cannot be directed to just one or a few tribal organizations. Local Indigenous advocates and providers face the challenge and opportunity of serving Indigenous community members across these tribal and cultural distinctions.

The Challenges of Data Advocacy

While the Indigenous communities in the Los Angeles region are diverse in origin and language, one common challenge is the limits of current, large-scale data systems like the American Community Survey (ACS) to enumerate and understand Indigenous communities. Because Tongva citizens are few in number and not federally recognized, the ACS and other federal datasets do not capture their presence. While Tongva tribal organizations have private lists of their citizens, these organizations’ competing claims to tribal leadership make it difficult to enumerate all Tongva residents in Los Angeles. In the case of Indigenous migrants, data analyses often group those communities in with the broader Latinx population, thereby rendering these migrant communities invisible in the numbers and narratives.

It is necessary for data analysts and demographers to partner directly with community organizations to better understand the particular circumstances that these Indigenous communities face and the solutions that are most effective for directing resources and policies to access safe and affordable housing.

Conclusion

Of course, these topics cover just a fraction of the circumstances and challenges that Indigenous Angelenos face around housing equity. The devastating January 2025 fires throughout Los Angeles County have destroyed thousands of homes and displaced entire communities, while threatening to raise rents for all Angelenos across the region. Local officials must ensure an inclusive, equitable recovery process that supports the thousands of working families suffering from the financial, health, and emotional consequences of the fires.

Core Resources

1 Spanish colonizers named the Tongva "Gabrieliños," but modern-day Tongva organizations usually refer to themselves as "Gabrielinos." In this analysis, we adopt the Tongva spelling of the term.