Regional Snapshot: Indigenous Residents in the Seattle, Washington Metropolitan Area

Note: This article is not intended to be a comprehensive survey or study of Indigenous residents in the Seattle region. Rather, these regional snapshots provide a few examples of recent policy changes, Indigenous-led housing and land campaigns, and/or population changes relevant to our overall analysis. Indigenous populations are diverse in makeup, and different regions of the US have different local histories of Indigenous colonization, migration, and/or political representation. Focusing on four individual regions helps to illustrate some of these regional differences and the unique character of local Indigenous housing politics.

We encourage you to learn more about Seattle’s Indigenous communities from the tribal governments and organizations active in the Pacific Northwest.

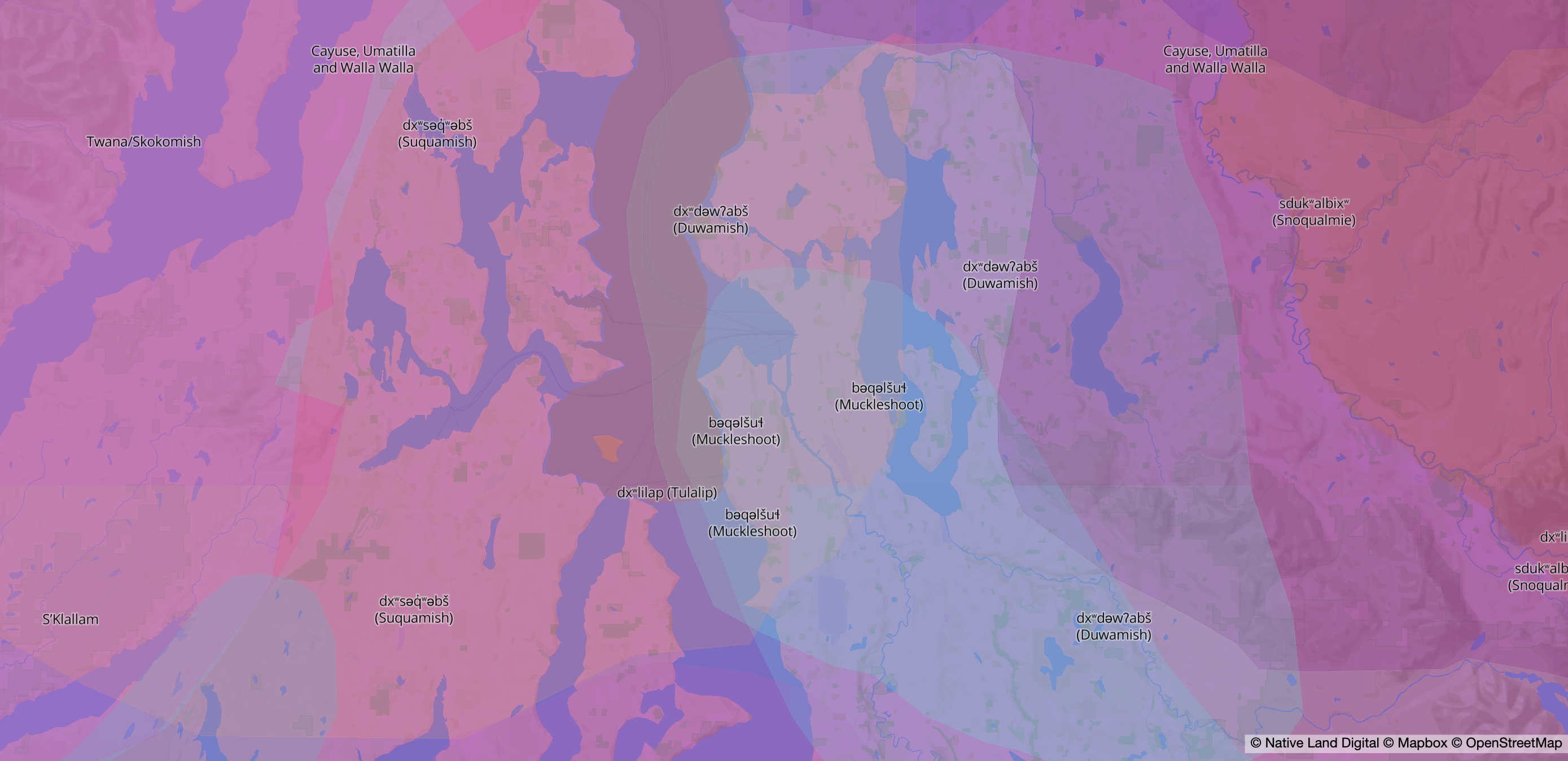

Territorial map of nations and tribes indigenous to the Seattle metropolitan area. Source: Native Land Digital. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

The Seattle metropolitan area (King, Pierce, and Snohomish counties) is home to over 160,000 residents who identify as Indigenous, the sixth-highest total among US metros. Indigenous residents make up 4 percent of the metro population, the eighth-highest Indigenous population rate in the US. The Indigenous population is also diverse: only 5 percent of Indigenous residents identify with the Coast Salish, a multiethnic group of tribes who originally inhabited the lands surrounding the Puget Sound and adjacent waterways. Indigenous renters in the Seattle metro area have relatively higher wages, with the sixth-highest median household income ($63,152 as of 2022) and the fourth-highest individual median wage ($20.44) among Indigenous populations in the metro US.

However, higher wages do not translate into greater rental affordability. With the relatively high costs of living, as of 2022, only one zip code (in and around the tiny community of Ashford, the southernmost area of the region) had a median market rent that would not cost-burden the median Indigenous rental household. A 2022 statewide report on housing needs for Indigenous residents noted that Indigenous residents in the Seattle area experienced houselessness at disproportionately high rates: 15 percent of all unhoused people were American Indians or Alaska Natives. Many residents suffer from intergenerational trauma and emotional distress rooted in the long-term dispossession, displacement, and forced assimilation of Indigenous communities. At the root of the crisis is the underfunding of both the continuum of care (rapid rehousing, permanent supportive housing, shelters) and culturally affirmative service providers best suited to work with Indigenous residents who are struggling.

Seattle has a rich history of Indigenous-led urban resistance and activism, spanning back to the earliest periods of Western colonization. While some of the region’s Indigenous inhabitants are engaged in struggles around federal tribal recognition and land sovereignty, other Indigenous leaders have taken innovative community development strategies for the housing and houselessness crisis among Indigenous residents. Some key examples of modern-day advocacy and community building are below.

Duwamish Struggles Over Federal Recognition

The original inhabitants of the Seattle metropolitan area were the Duwamish Nation, one of the peoples under the umbrella of the Coast Salish. Duwamish contact with American and European colonists remained sparse until the 1850s, when the US established the Washington Territory and encouraged settlement of the region. In 1855, the US government signed the Treaty of Point Elliott with Duwamish Chief Si'ahl (Seattle) and other local tribal leaders, ceding tens of thousands of acres of land in exchange for reservations, money, and access to traditional fishing and hunting areas. In the following years, Duwamish communities who opted not to resettle on reservation land were gradually displaced and forced out as American settlers continued to populate the region.

Many descendants of the Duwamish Nation are citizens of the federally recognized tribes who occupy parts of the Seattle metropolitan area and the surrounding counties, including the Lummi, Muckleshoot, Puyallup, Suquamish, Swinomish, and Tulalip tribes. However, the US government does not recognize the Duwamish per se as its own distinct tribe, despite prolonged efforts by the Duwamish Tribal Organization (DTO), which claims tribal leadership under a century-old constitution. In 2022, the Council sued the US Department of the Interior to compel another review of its petition for recognition; the suit is still pending. Notably, the opposition to recognition of the DTO includes the Muckleshoot and other federally recognized tribes in the Seattle region, who contend that they are the rightful descendants of the original Duwamish and repudiate the DTO’s claims to leadership.

Local Land Back and Rematriation Movements

In recent years, Duwamish leaders and other tribal organizations have led Land Back campaigns, which aim to receive or purchase plots of land from public or private entities and restore Native cultural, political, and economic stewardship of the land. These Land Back campaigns have led to a few successful land returns, or rematriations:

- In 2017, a group of non-Duwamish allies established the Real Rent Duwamish program, which encourages local residents to make a local recurring donation to Duwamish Tribal Services to support land purchases and other programs. As of 2022, Real Rent had upwards of 20,000 monthly donors.

- In 2020, the Shared Spaces Foundation partnered with the Duwamish Tribal Organization on a long-term plan for the rematriation of the Heron’s Nest, a 3.5-acre parcel next to the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center in West Seattle. The Foundation is currently leasing the land on behalf of the Duwamish Tribal Organization, while partnering with other community organizations to restore the land and raise funds to eventually purchase the plot. Heron’s Nest hosts workshops and educational sessions on land restoration and preservation, and plans for the land include an outdoor kitchen, urban farm, and aquaculture pool.

- In 2022, the yəhaw̓ Indigenous Creatives Collective, a queer-led, intertribal nonprofit arts organization, purchased 1.5 acres of land in the Rainier Beach neighborhood of South Seattle. The collective has been restoring the land for use in arts and cultural programming, and it purchased an adjacent home in 2024 with plans to convert the building into an Indigenous arts center.

Native-Led Housing and Houselessness Strategies

The Chief Seattle Club, an intertribal nonprofit service provider and community developer, has taken a leading role in local solutions to Indigenous housing unaffordability and houselessness. The organization operates housing at multiple points in the houselessness continuum of care, including rapid rehousing, transitional housing, and permanent supportive housing, in addition to rental assistance and other supports for Indigenous households at risk of eviction. In 2022, the Chief Seattle Club opened ʔálʔal, an 80-unit affordable housing complex in the Pioneer Square neighborhood of downtown Seattle and the first Indigenous housing project in the region. All of the apartments are reserved for extremely low-income households (those with income at or below 30 percent of the area median income). The majority of the units are designated for formerly unhoused residents, with 10 units set aside for Indigenous veterans. The complex also includes a federally qualified health center, spaces for cultural programming, Indigenous art, and a ground-floor cafe.

Local Indigenous leaders have pointed to housing as a key element in a longer healing process for Indigenous residents suffering from the lasting financial and psychological harms of colonization. Interweaving Indigenous cultural practices into supportive housing helps to cultivate a welcoming and restorative space for Indigenous residents who might otherwise feel unwelcome. Projects like ʔálʔal offer a potential template for Indigenous communities in other regions to address housing crises with an explicitly trauma-informed, culturally affirmative approach.