Regional Snapshot: Indigenous Residents in the Tulsa, Oklahoma Metropolitan Area

Note: This article is not intended to be a comprehensive survey or study of Indigenous residents in the Tulsa region. Rather, these regional snapshots provide a few examples of recent policy changes, Indigenous-led housing and land campaigns, and/or population changes relevant to our overall analysis. Indigenous populations are diverse in makeup, and different regions of the US have different local histories of Indigenous colonization, migration, and/or political representation. Focusing on four individual regions helps to illustrate some of these regional differences and the unique character of local Indigenous housing politics.

We encourage you to learn more about Tulsa’s local Indigenous communities from the Osage, Cherokee, and Muscogee (Creek) Nations, whose reservation lands overlap with the majority of the Tulsa metropolitan area.

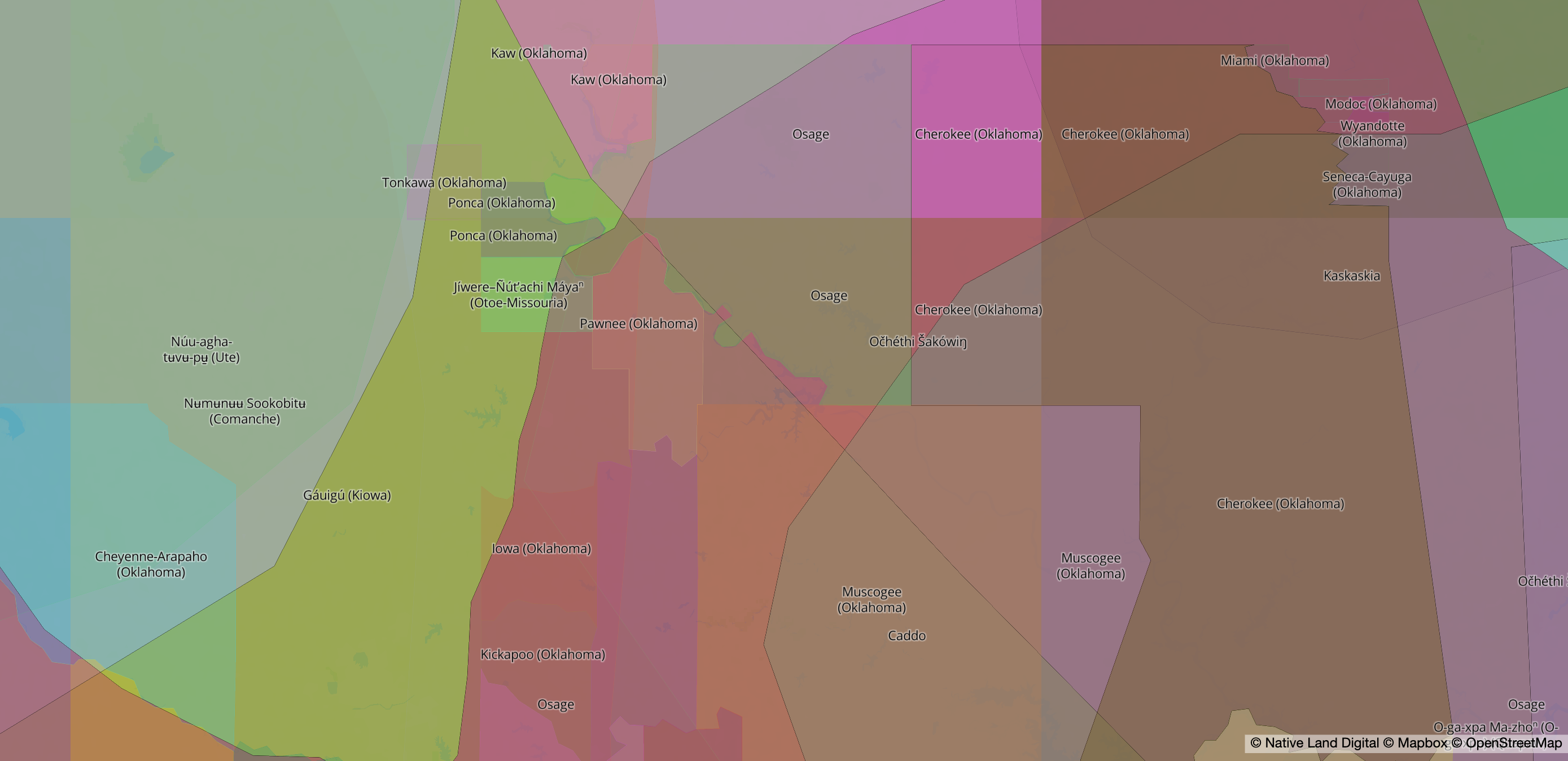

Territorial map of nations and tribes indigenous to the Tulsa metropolitan area. Source: Native Land Digital. Retrieved August 8, 2025.

With nearly 15 percent of residents identifying as Indigenous, the Tulsa, Oklahoma metropolitan area (Creek, Okmulgee, Osage, Pawnee, Rogers, Tulsa, and Wagoner counties) has the largest Indigenous population rate for any major US metro area outside of the Honolulu region. With the exception of Pawnee County, the entire metropolitan area lies on reservation land, split between the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Osage Nations.

This concentration of Native American residents and tribal lands is the result of the US government’s efforts to remove the vast majority of Native Americans from east of the Mississippi River over the course of the 1890s. In the mid-1800s, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole Nations were forced out of their ancestral homes in the Southeastern US and displaced into the so-called “Indian Territory” in current-day Eastern Oklahoma, a process known as the Trail of Tears. Oklahoma achieved statehood in 1907 by joining Indian Territory and the western half of the state (then known as Oklahoma Territory) into a single entity. As we explore below, this legacy has become newly relevant to state and local politics in recent years.

Among the 76 US metropolitan areas in the analysis, the Tulsa region was the second-most affordable for Indigenous renters, with 24 percent of zip codes featuring a median market rent that would not create a cost burden for a median-income Indigenous rental household. Only the Memphis, Tennessee metropolitan area had a higher share of affordable neighborhoods (25 percent). However, relatively lower rental costs are offset by low wages as well: the median wage for Indigenous workers was just under $16 per hour, the 48th highest total out of the 76 metros. Many Indigenous and non-Indigenous renters alike face a host of challenges in finding safe affordable housing.

Because the region largely overlaps with reservation lands, the Tulsa metropolitan area is unique among US metros, with the three Indigenous nations exercising some degree of tribal sovereignty in criminal prosecution and land use decisions within the region. Despite aggressive approaches among some tribal leaders to address Indigenous housing issues, the state’s landlord-friendly tenant policies serve as a barrier to many Indigenous renters’ well-being. We explore some of these issues below.

Tribal Sovereignty in Oklahoma

In 2020, the US Supreme Court issued a ruling in McGirt v. Oklahoma with profound implications for tribal sovereignty in the state. The court ruled that Congress had never disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation’s 19th-century reservation land after annexing the state of Oklahoma, meaning that Muscogee land was “Indian country,” and the criminal prosecution of Native American residents on Muscogee land was the jurisdiction of federal, not state, courts. A subsequent ruling in the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals extended the McGirt decision, determining that the other reservations in the state had also not been disestablished, meaning that the entire eastern half of Oklahoma was tribal land.

While the McGirt case concerns the matter of criminal prosecution of Native Americans on tribal lands, Chief Justice John Roberts noted that the ruling could create subsequent legal struggles over governance in other domains. For instance, mortgage lenders could face challenges if tribal citizens who own land on tribal territory were not subject to the Oklahoma state courts in the event of a foreclosure. It is likely that future legal challenges will shape the judicial interpretation of McGirt in the years to come.

Cherokee-Led Approaches to the Housing Crisis

In 2024, the Cherokee Nation published a comprehensive assessment of housing needs for Indigenous and non-Indigenous residents living on tribal territory, which includes parts of Rogers, Tulsa, and Wagoner counties in the Tulsa metro area. According to the report, the area would need an additional 8,800 to 9,400 homes over the next decade, with over 6,000 of those units already needed to meet the current demand. There was a particularly acute need for extremely low-income housing, or affordable housing reserved for households making less than 30 percent of the area median income, with rising levels of overcrowded rental households and unsheltered houselessness across Cherokee tribal territory. While the Cherokee Nation needed to build housing of all types, the report also emphasized the importance of housing that could accommodate large multigenerational households, with grandparents, parents, and grandchildren living under the same roof.

For years, the Cherokee Nation has sought to address these challenges through a diversity of housing strategies. In 2024, Cherokee lawmakers passed a bill that permanently reauthorized funding for the Housing, Jobs and Sustainable Communities Act, originally signed into law in 2019. The law provides for a number of housing programs, including the construction of new units, home rehabilitations, lease-to-own programs, and neighborhood development projects like community centers. Tribal leaders note that these efforts are in part a response to the US government’s systemic underfunding of housing for Indigenous nations, as the housing crises in the region demanded a more aggressive, autonomous approach.

Affordability and Livability

While the Tulsa metropolitan area is one of the most affordable regions in the US for Indigenous renters, the Cherokee Nation’s report indicates that many of the region’s residents—Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike—face a host of housing challenges. As the Oklahoma Policy Institute (OPI) notes, the state’s policies strongly favor homeowners and landlords. Homeowners, who are disproportionately white, enjoy tax benefits like homestead exemptions that are unavailable to renters. Landlords can easily evict tenants, and tenants have few protections against landlord retaliation or harassment. OPI also advocates for a statewide right-to-counsel policy for tenants in eviction court, as tenants in Oklahoma have no guarantee of legal representation. An Open Justice Oklahoma analysis of eviction cases in Tulsa County determined that defendants were 75 percent more likely to remain in their homes if they had legal representation.

Beyond strengthening its policies, the Oklahoma state government also requires adequate funding and staffing to ensure housing equity. The state’s housing agencies have insufficient capacity to regulate landlord malpractice and enforce fair housing laws, making it likelier that Indigenous renters and other marginalized communities face unchecked discrimination in the housing market.