80 of the Bay Area’s 101 Cities Have No Black Leaders Among Their Top Elected Officials

Our analysis shows that regionwide, the share of top Black electeds parallels the share of the Black population. Yet, many cities including those with increasing Black populations lack Black elected leaders.

The nation faces two deadly and interrelated pandemics that disproportionately impact Black Americans: the coronavirus and systemic racism. Health co-morbidities due to environmental racism and occupational hazards undoubtedly play a role in the virus’s toll on Black communities, but so too does a deeply rooted concept embedded in the national consciousness that goes back to the original sins of our country: a hierarchy of human value that places Black and Native American people on the bottom and Whites at the top. This ideology contributes to racial inequities in nearly every facet of American life, including politics as detailed by the diversity of local electeds dataset maintained by the Bay Area Equity Atlas.

The landscape of Black local elected officials in the Bay Area varies substantially, according to our analysis of data on the diversity of elected officials from 2018 and 2019. Regionwide, the share of Black local elected officials equals the share of Black residents – an indicator of representativeness – but Black residents are completely left out in 80 out of the region’s 101 municipal governments.

Beneath the regional level, however, some Bay Area cities did improve on the representativeness of their top electeds, while others fell behind. This post shares key findings from our analysis of how the region’s 101 cities are doing on this measure, which is calculated based on the share of top local elected officials who identify as Black. Note that the city electeds include both city council and county elected officials (supervisors and DAs) because county electeds also represent city residents. This means that the typical city/town has 11 electeds included in the analysis (5 council members, 5 county supervisors, and one county district attorney).

As Black Residents Move Inland, Some Suburbs Saw a Rise in Black Politicos

The Black population in the Bay Area declined by nearly 42,000 people from 2000 to 2015 – an 8 percent drop. And within the region, Black residents have moved outward from the regional core to inland communities. From 2000 to 2018, for example, the city of Richmond saw a 16 percentage-point decline in the Black population share from 36 percent to just 20 percent. Cities like Antioch and Oakley in Contra Costa County and Rio Vista in Solano County, on the other hand, saw five percentage-point plus increases in their Black populations.

Our most recent analysis of Black local elected officials partially reflects these shifting demographics. By 2020, two of the top three cities with the most Black representation in local elected governments – Pittsburg and Antioch – are located in Eastern Contra Costa County.

Pittsburg, Richmond, and Antioch each elected an additional Black representative in 2018. The city of Pittsburg had five Black elected officials (at the city and county level), but that number increased to six by 2020 when Pittsburg became the only city in the region where the majority of local elected officials are Black. Richmond also gained a Black city council member in the 2018 election, and by 2020, 46 percent of the city’s local elected officials were Black. The city of Antioch, where 36 percent of top local electeds are Black, surpassed Oakland to round out the top three.

At the same time, historically Black cities in the coastal core of the Bay Area with long histories of Black community organizing saw steep declines in the share of Black residents. Oakland, Richmond, and East Palo Alto experienced double-digit decreases in the share of Black residents from 2000 to 2018. Previous studies describe in great detail this reorganization of racial segregation in the Bay Area, and the findings from the diversity of electeds database suggests that outer suburbs in Contra Costa County are faring decently when it comes to Black representation in local elected government.

Black Residents Underrepresented Among Top Electeds in Vallejo, Fairfield, San Leandro, and Vacaville

A few cities, however, are notable for their lack of Black representation at the city and county levels. The first is the city of Vallejo, where one in five residents are Black but only 8 percent of local elected officials are Black. This is despite the fact that the city elected a Black city councilmember in 2018. Black residents are also underrepresented in the city of Fairfield, where Black residents make up 14 percent of the city’s population but are just 9 percent of elected officials.

San Leandro, Berkeley, and San Pablo, each lost a local Black elected official in 2018. Today, just 15 percent of local elected officials in San Leandro are Black. The city of Vacaville, which has roughly the same Black population share as East Palo Alto, lacks any Black representation in local government at the city or county level.

Two other cities have relatively small Black population shares but saw sizable increases in Black residents despite no Black representation among top local electeds. The city of Rio Vista in eastern Solano County saw a six percentage-point increase in the Black population since 2000 but lacks Black representation in top local elected positions. The San Mateo County city of Brisbane similarly saw an increase in the Black population share of five percentage-points but none of city or county top elected officials identify as Black.

Two Peninsula Cities Gain Big and Make History

Our analysis also reveals that Menlo Park saw the largest increase in Black representation from 2018 to 2020. In 2018, Menlo Park was one of 59 cities without any Black representation in top local elected offices. But with the election of Mayor Cecilia Taylor and Vice Mayor Drew Combs in 2018, the city gained two additional Black representatives, making up 18 percent of top local elected officials.

The neighboring Peninsula city of Los Altos made history in 2018, electing their first Black city council member: Vice Mayor Neysa Fligor. After losing her 2016 election bid by just 6 votes, Vice Mayor Fligor came back in 2018 to win every precinct in the city. The Vice Mayor is also the youngest councilwoman on the only all-female city council in the region.

A Clear Need for Action

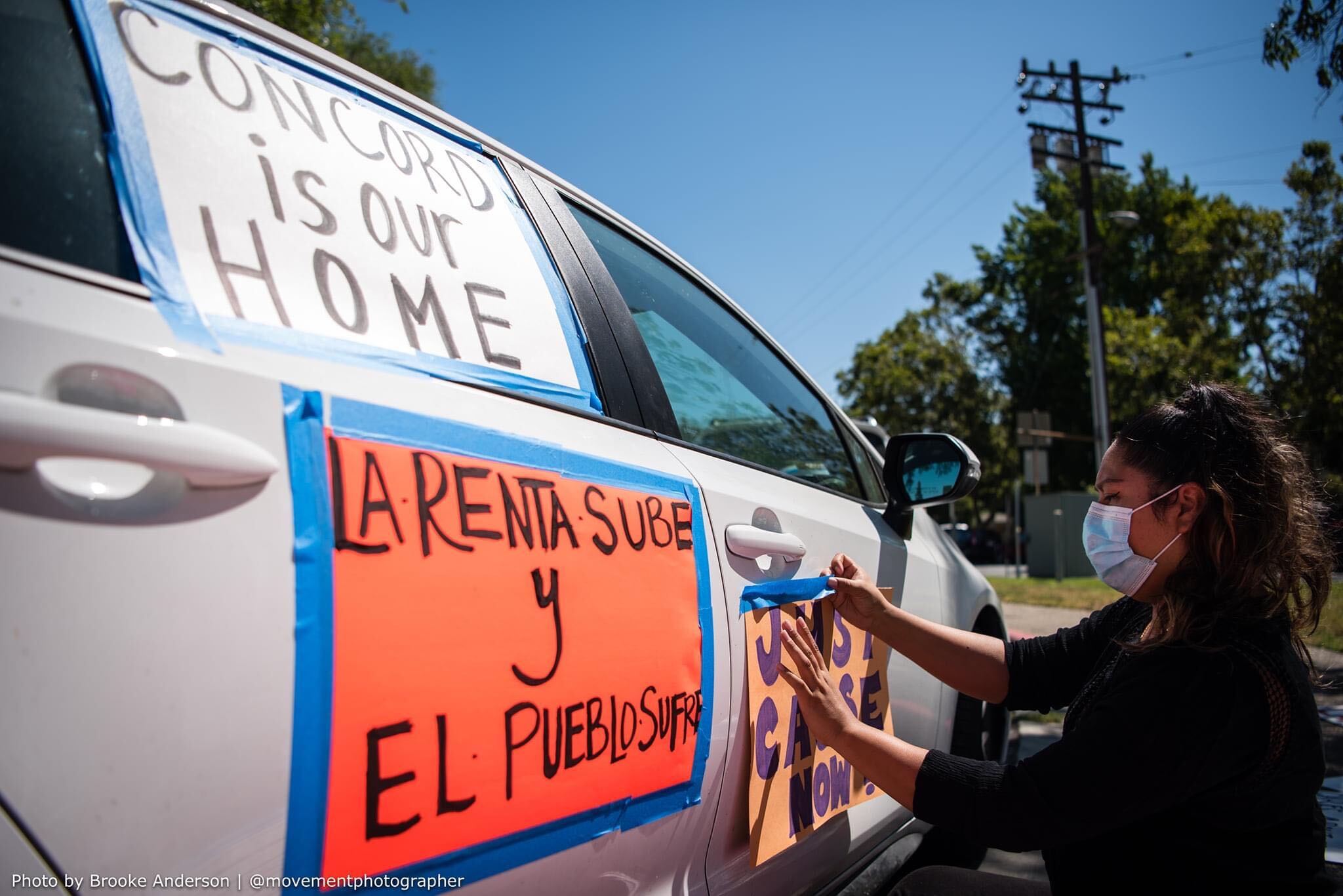

While representation does not ensure the passage of more equitable policies, it matters for political power. Local officials hold considerable power over the everyday lives of Bay Area residents, including local police and sheriff’s departments, and they ought to reflect the diversity of the communities they serve. Improving on this indicator involves directly addressing the multiple barriers that hold Black residents back from running for political office whether they are economic, institutional, or political. It also requires a bold agenda to curb Black displacement in the region and the passage of policies that allow Black residents, especially low-income residents and renters, to stay put.

Even before the coronavirus epidemic and nationwide uprisings against racial injustice, working class people in the region were struggling to make rent, find affordable childcare, and secure living-wage jobs. The historic spike in layoffs and unemployment brought about by COVID-19 has only exacerbated economic insecurity. Many families are struggling to make ends meet and are focused on finding work and paying bills rather than increasing political involvement.

But political inclusion is a critical part of building a more equitable region, and we, along with our partners at Bay Rising, lift up the following recommendations to move us towards just and fair inclusion into a region where all can participate and prosper:

- Local governments (cities, towns, and counties) should pass structural reforms including public campaign financing and campaign finance reform to curtail corporate contributions, secret Super PACs, and “pay-to-play” politics.

- Local and national philanthropies and corporations should fund equity-oriented leadership development programs, like Urban Habitat’s Boards and Commissions Leadership Institute that prepare people from underrepresented communities of color to effectively engage in public policy.

- Policymakers and funders should support voting reforms and civic engagement efforts that increase voter registration and turnout among underrepresented communities, especially in local elections.