We are excited to introduce new data on the National Equity Atlas: our median wages indicator is now disaggregated by gender as well as race. Here we will describe what the indicator measures, discuss some related national trends, and show you how to get more information on the gender pay gap and what can be done to address it.

What it measures

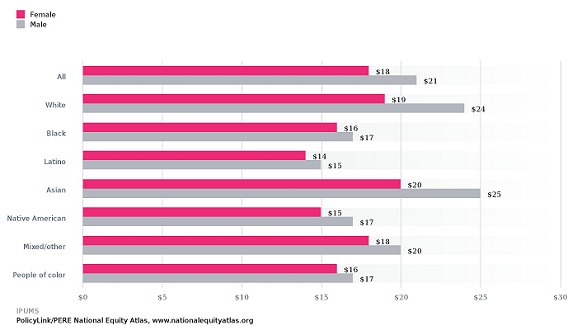

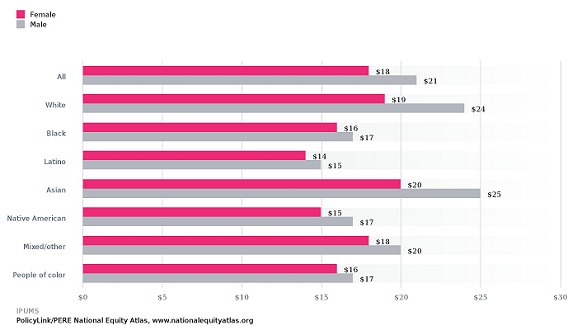

This indicator reports the median hourly wages (in 2012 dollars) of full-time wage and salary workers ages 25–64, by gender and race/ethnicity. As the chart below illustrates, you can compare wages by gender both within and between racial groups, and track trends over time with data going back to 1990.

Above: Median Hourly Wage by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, United States

Above: Median Hourly Wage by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, United States

National trends

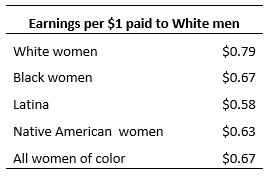

Nationwide, full-time working women now earn $0.86 for every dollar earned by their male counterparts, compared to $0.71 in 1990; this seems like encouraging progress, but according to a study by the Economic Policy Institute, 40 percent of that progress is explained by declining wages among men. The data in the Atlas support this conclusion: while women’s wages have risen by about 6 percent over the last few decades, men’s wages have fallen by nearly 13 percent. In addition, research has shown that the women continue to earn less than men not only because of differences in education, occupation, and family needs, but also as a result of gender discrimination and bias in the workplace. Across the U.S., White women earn about $0.79 for every dollar earned by White men, and the gaps are even larger for most women of color:

As the new data in the Atlas clearly indicate, gender pay gaps can’t be understood in isolation from racial pay gaps. Exploring some national trends can show how these dynamics are interconnected:

- Overall, men earn more than women in all 50 states, all of the 150 largest metro areas, and 98 of the 100 largest cities. Nationally, men earn more than women within each racial group, and this trend holds true for the majority of metros and cities as well.

- White women earn more than women of color in all 50 states, all of the 150 largest metros, and all but one of the 100 largest cities (excluding Hialeah City, Laredo City, and Portland-South Portland-Biddeford, ME Metro, for which there are insufficient data to make such a comparison). These inequities persist even among women with similar levels of educational attainment. College-educated women of color, for example, earn an average of $23 per hour, compared to $28 per hour for White women with the same level of education.

New in the Atlas: City-level data

The greatest gender wage equality has been achieved at the city level, particularly in places where White women earn the most and men of color earn the least compared to White men—meaning the cities with the smallest gender pay gaps have some of the steepest racial pay gaps in the country.

Let’s take a closer look at Los Angeles as an example. In L.A., one of only two cities in the U.S. where women’s median hourly wages are slightly higher than men’s, men of color earn less than half the pay of their White counterparts:

Above: Median Hourly Wage by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, Los Angeles

White men are paid dramatically more than all other workers in the city of Los Angeles: White women earn $0.83, women of color earn $0.50, and men of color earn just $0.47 for every dollar earned by White men. Differences in education, occupation, and experience account for some but not all of these disparities; this is why the disaggregated data presented in the National Equity Atlas and other data tools like Clocking In (produced by Race Forward) are so important and powerful: they can help advocates and policymakers push forward creative, multidimensional solutions by showing how economic and social inequities are multilayered.

Strategies for reducing gender wage gaps

It is clear that city, state, and national leaders should focus on strategies that will address both gender and racial wage gaps, such as increasing the minimum wage, enacting living-wage laws, guaranteeing paid sick days, preventing wage theft, ensuring fair scheduling, and targeting economic development and workforce efforts to grow high-opportunity sectors that provide pathways to good jobs for people without four-year degrees. More specifically, strong protections against gender wage discrimination, like California’s new equal pay statute, can help ensure that workers are fairly compensated regardless of their gender.

How to get the data for your community

Visit the National Equity Atlas to explore data for your city, region, or state:

1. Click on Indicators in the navigation bar;

2. Select the Wages: Median indicator under Economic Vitality;

3. Select By gender in the breakdowns underneath the chart.