Rent Debt in America: Stabilizing Renters Is Key to Equitable Recovery

Our rent debt dashboard, produced in partnership with the Right to the City Alliance, equips policymakers and advocates with data on the extent and nature of rent debt in their communities to inform policies to eliminate debt and prevent the specter of mass eviction.

By Sarah Treuhaft, Michelle Huang, Alex Ramiller, Justin Scoggins, Abbie Langston, and Jamila Henderson

Mounting rent debt and the potential for mass eviction is one of the most pressing equity issues created by the Covid-19 pandemic. The vast majority of renters who are in debt are low-wage workers — disproportionately people of color — who’ve suffered job and income losses due to the pandemic. As of August 3rd, the federal eviction moratorium was temporarily extended to October 3rd for a more narrow subset of renters. While this extended order will cover the majority of renter households, when the order expires at the beginning of October, the renter households that still hold debt and lack protection by state or local moratoria will be at imminent risk of eviction and homelessness. Allowing this eviction tsunami to take place would be a moral travesty and a policy failure that would deepen inequities at a moment when the federal government has prioritized addressing systemic racism and ensuring an equitable recovery.

To inform policymaking and advocacy to prevent eviction and eliminate rent debt, the National Equity Atlas and the Right to the City Alliance launched a rent debt dashboard in April 2021 with near real-time data on the number and characteristics of renters behind on rent for the US, most states (currently 40 states), and 15 metro areas.* The dashboard also provides estimates of the amount of back rent owed for these geographies, as well as estimates for the number of households with debt and the amount owed for all counties in the states. Drawing current data from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey and the University of Southern California Center for Economic and Social Research's Understanding Coronavirus in America survey, the dashboard data is refreshed approximately every two weeks. Find our full methodology here.

Born out of the need for accessible, current data to inform local and state campaigns, the dashboard was produced in partnership with the Right to the City Alliance, a network of community-based organizations working in 45 cities and 26 states to prevent displacement, expand affordable housing, and build just, sustainable cities for all.

This analysis shares key insights from the dashboard, based on the June 23 - July 5 Pulse survey, along with action steps that local, state, and federal policymakers can take to stabilize the people most negatively impacted by the pandemic and facilitate equitable recovery by addressing the challenge of rent debt.

This is an update to our April 21, May 25, and July 7 analyses. We will be updating our dashboard and this analysis after the August 11 Pulse data release.

Rent debt continues to be a significant issue, with 6.4 million renter households behind on rent.

As of the first week of July 2021 6.4 million renters — 15 percent of all renter households — were behind on their rent payments. The federal eviction moratorium from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention enacted in September 2020 provided these renters with some protection from eviction but will expire on October 3. And even now, the temporary eviction moratorium order does not apply to all renter households who might be at risk. A few states and cities still have moratoria banning eviction for nonpayment of rent. However, most renters with arrears live in the vast majority of states and cities that do not have moratoria and they are at imminent risk of eviction and homelessness. As a point of comparison, nearly 8 million households lost their homes to foreclosure due to the 2008 financial crisis.

The Pulse survey has been asking the question “Is this household currently caught up on rent payments?” every two weeks since August 2020. Nationally, the current share of renters with debt is down from a high of 19 percent in mid-January, but remains far higher than the pre-pandemic baseline. While data on rent debt is sparse, the 2017 American Housing Survey found that about seven percent of renters were unable to pay some or all of their rent.

South Carolina and Georgia have the highest share of renters with arrears among the 40 states analyzed.

The share of renters who are behind on rent is much higher than the national average in some states and metro areas. Among the 40 states with sufficient data to include in our analysis, South Carolina has the highest share of renters with arrears (28 percent), and at least 20 percent of renters are behind in the states of Georgia, New York, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee. Idaho and Montana have the lowest shares of renters with debt, at 6 and 4 percent, respectively.

Among the 15 metros included in the Pulse survey, New York and Riverside have the highest share of renters with debt (24 percent), followed by Seattle (21 percent), and Atlanta and Philadelphia (both at 19 percent). Phoenix and Miami are tied for the lowest share of renters in arrears among the 15 metros (8 percent).

Nationally, we estimate that rent debt amounts to about $21 billion.

According to our estimates, households that are behind on rent owe $3,300 on average, for a total of $21.3 billion nationwide. As this average suggests, the majority of households who are behind owe one or two months of back rent. However, a smaller but not insignificant number of renters have not been able to pay rent for many months and owe much larger amounts. Our analysis of the University of Southern California’s Understanding Coronavirus in America national survey finds that approximately 28 percent are one month behind, 22 percent are two months behind, 15 percent are three months behind, and the remaining 35 percent are more than three months behind.

The average amount owed depends primarily on local housing costs, so it varies significantly across states and metros. Among states, Hawaii has the highest average rent debt per behind-household ($5,600), while Arkansas has the lowest ($2,100). At the metro level, San Francisco and Washington DC have the highest average debts ($5,800 and $5,200, respectively), while Detroit has the lowest average debt by far ($2,500), followed by Phoenix ($3,200).

Our national estimates of rent debt fall somewhere in the middle of existing projections in terms of total debt, and on the lower end in terms of per household amount. In January, Moody’s Analytics projected that 6.3 million renters would owe a total of $33 billion in rent debt by March, at an average of $5,282 per household. Stout Analytics estimated that between two and five million renter households owed between $13 and $24 billion as of January. Both Moody’s and Stout used the Pulse survey to inform their estimates of the number of households behind. Using a very different methodology based on modeling employment losses, income supports, and spending choices at the household level, and not incorporating the Pulse survey data, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimated that 1.8 million renter households would owe $11 billion in rent in March, at approximately $6,100 per household.

With the incipient recovery, the number of renters with debt has declined nationwide since its peak in January, but has remained at 14 percent since late March. Most states and metros are following this decline.

Nationwide, the share of renters with debt trended downward from a high of 19 percent in January to 14 percent in late March, and has held steady around 14 percent for the past couple of months. Nearly all states and metros followed this general downward trend since their peaks. Between January and the beginning of July, the rates of renters behind on rent rose in only nine states, the District of Columbia, and four metro.

Among states, Georgia saw the largest spike in arrearages (from 18 to 25 percent behind), followed by Oregon (from nine to 12 percent). Missouri saw the most improvement (from 27 to 12 percent behind).

Among metros, Seattle saw the highest increase (from 13 to 21 percent behind). Dallas saw the greatest decrease (from 27 to 10 percent).

The vast majority of those who are behind on rent are low-income households who’ve lost jobs and income during the pandemic.

Today’s rent debt crisis is entirely a consequence of the pandemic’s economic fallout: 68 percent of those who were behind on rent in May had lost employment income at some point during the pandemic, according to the May 12-24 Pulse survey which asked respondents this question. As our other research has shown, low-wage workers, who are disproportionately workers of color, were hardest hit by pandemic job losses and are most likely to suffer from rent debt. Among households with rent debt, 81 percent are low-income (with earnings less than $50,000 per year) and 64 percent are renters of color. The majority (51 percent) are currently unemployed.

Renters have made tremendous sacrifices and tradeoffs to stay current on rent, including foregoing medical care, delaying payment of other bills, eating cheaper (and potentially less healthy) food, and voluntarily moving in with friends and family — increasing risk of Covid-19 exposure while losing their housing stability. One of the most surprising facts in the data is the high share of low-income renters who are paid in full: Among low-income households that lost employment income during the pandemic, 73 percent were not behind on rent as of May (also according to the May 12-24 Pulse survey).* This underscores how paying rent has remained a top priority for all renters throughout the pandemic, despite the moratoria on evictions.

Rent is not the only debt accumulating for renters.

While our analysis focuses on back rent, renters’ pandemic debt crisis extends far beyond their obligations to their landlords. Many renters are borrowing from family and friends or taking on other forms of debt in order to make rent and pay for household expenses. Among households behind on rent, 46 percent borrowed from friends or family to pay rent, compared with just 15 percent of households current on rent. About 30 percent of all renter households, whether behind or current on rent, used a credit card (or some other form of debt) to pay rent. Many are behind on other bills, such as utilities or car payments. A survey of water debt in California found that 1.6 million households owed $1 billion on water bills — $500 on average.

Renters of color have been disproportionately impacted by the pandemic and are more likely to owe back rent, making them more vulnerable to eviction risk.

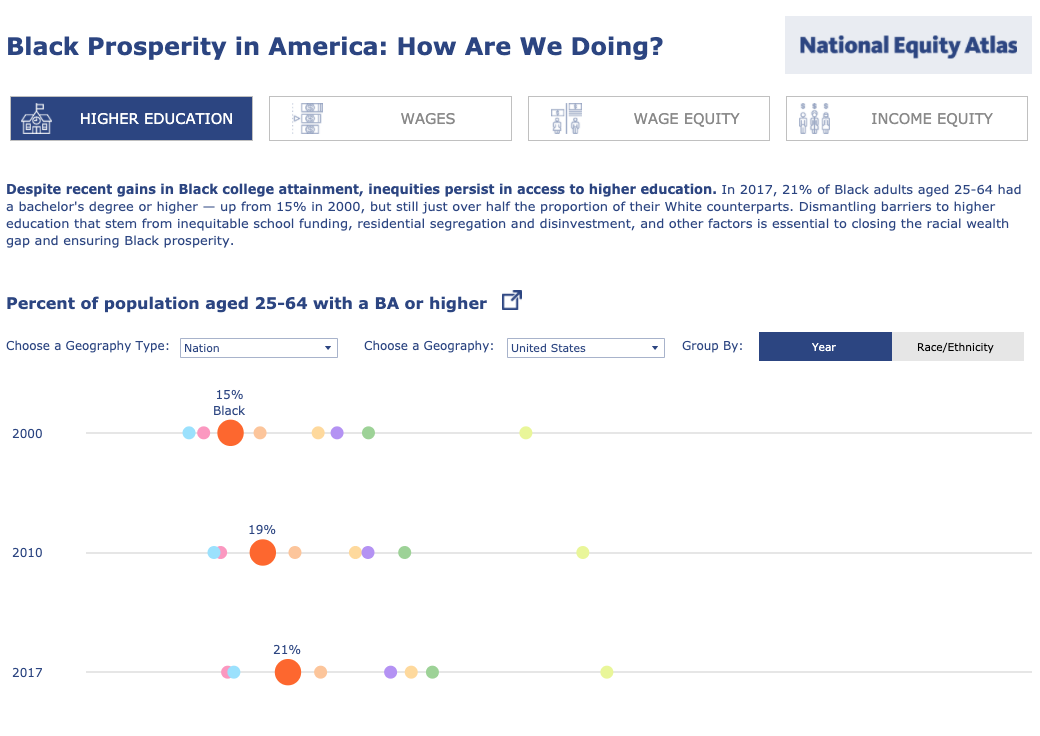

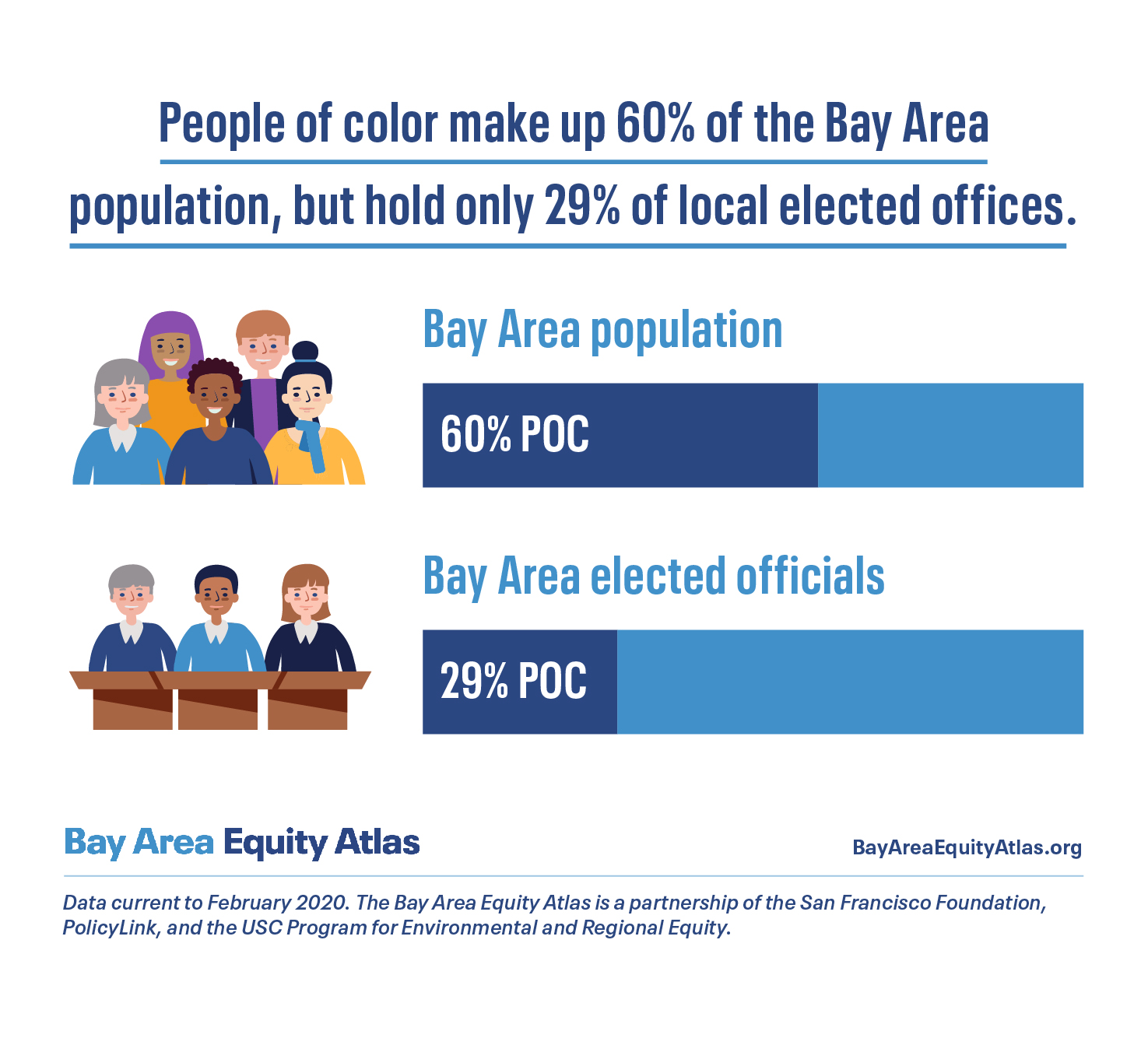

In the United States, renters are already a more vulnerable population as a whole: they have little housing security, paltry savings, and few legal protections from exorbitant rent increases or eviction (outside of a few states and cities with strong tenant movements). Historic and continuing housing and lending discrimination, as well as systemic inequities in our labor market, have contributed to large racial inequities in homeownership. Atlas data show that seven in 10 White households own their homes while the majority of Black, Latinx, and multiracial households rent.

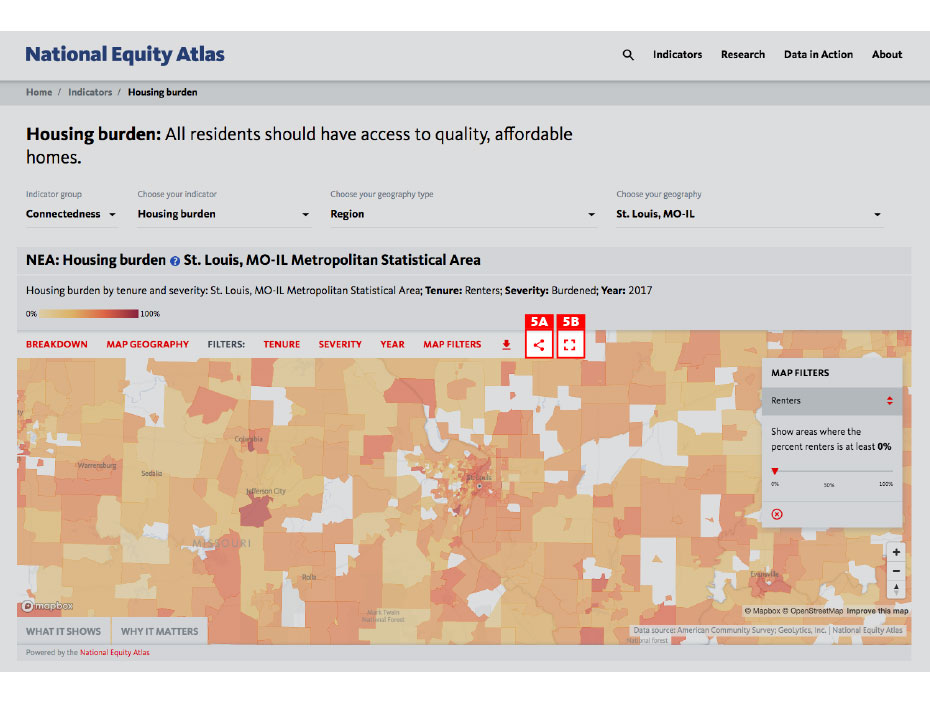

The challenge of unaffordable rents and flat wages add to this underlying housing insecurity among renters. Renters were already in crisis when the pandemic began: about a third of White renters and just under half of Black and Latinx renters were both economically insecure (earning less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level) and rent burdened (paying more than 30 percent of their income on rent). Gender is another important axis: women of color are most likely to be rent burdened, and disproportionately face eviction.

Covid-19 added yet another layer of inequity to these preexisting disparities. Today, 24 percent of Black renters, 17 percent of Asian or Pacific Islander and Latinx renters, and 18 percent of multiracial renters are behind on rent, compared to 9 percent of White renters.

Eliminating Rent Debt is an Equity Imperative and a Moral, Economic, and Public Health Necessity

Today’s rent debt crisis is a microcosm of the wretched inequality of the pandemic: millions of renter households – most of them people of color – now face the burden of owing back rent due to a public health crisis that had extremely concentrated negative economic impacts on low-wage workers. These unequal consequences are not random, but the predictable result of past policies that left millions of families with no savings to draw upon in the face of an economic shock, as well as the failed early policy response to the pandemic. Although the CARES Act provided important unemployment benefits and cash assistance as well as an eviction moratorium that helped many pandemic-impacted renters, undocumented and mixed-status families were ineligible for assistance and the moratorium ended in July, leaving renters unprotected until the CDC enacted its moratorium in early September. Moreover, absent meaningful financial assistance to pay back rent, the moratoria simply delay eviction. Yet, the federal government provided no rent relief until December, nine months into the pandemic.

The magnitude of rent debt is a crisis in and of itself and the leading indicator of a potential eviction tsunami that would be a humanitarian disaster. Rent debt adds a heavy burden onto families who are already financially insecure and struggling during the pandemic, further limiting their choices and creating additional stress. It’s also contributing to the growth of the racial wealth gap: while renters, predominantly people of color, currently hold $20 billion in debt, homeowners, who are predominantly White, saw a $1.9 trillion increase in their home equity from the first quarter of 2020 to the first quarter of 2021 as competition for a constrained supply of homes drove prices up. At a time when racial equity is at the forefront of the policy debate, eliminating rent debt that has unfairly and unequally accrued for people of color should be an urgent priority.

Clearing rent debt is also key to staving off the specter of mass eviction, which would directly harm economically vulnerable families and their communities and have long-term ripple effects throughout our economy. Eviction has significant negative consequences for mental and physical health, educational outcomes, and household finances. Some evicted families and individuals would become homeless, with devastating consequences for long-term health and well-being as well as significant costs for local governments.

The health impacts of eviction and homelessness are even more severe during a pandemic. Research during the pandemic found that states that allowed evictions to proceed had more Covid infections and deaths than those with eviction moratoria. Although the vaccination campaign is in full swing and Covid cases are low in most states, there are hotspots with high infection rates and the longer-term picture remains uncertain.

Forgiving rent debt is also essential to an equitable and people-centered recovery: one in which those hardest-hit by the pandemic can fully participate and thrive.

For an Equitable and Just Recovery, Policymakers Must Clear Rent Debt and Prevent Eviction

Recognizing the catastrophic impact of mass eviction, policymakers have responded, albeit belatedly, by enacting eviction moratoria and establishing rent relief funds. The federal CDC eviction moratorium scheduled to expire last month was temporarily extended through October 3 for most renter households, and the American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in January provided $21.5 billion for rental assistance programs as well as $350 billion in fiscal support for state and local governments, some of which could be allocated toward debt relief. The December 27 coronavirus relief bill also provided $25 billion in funding for rental assistance.

With the federal moratorium expiring in just a couple months and many state and local emergency rent relief programs supported by the ARP just getting off the ground, there is an urgent need to clear the debts of all tenants in need to prevent mass eviction. Throughout the pandemic, rent relief programs have not been reaching all of those in need. These programs must be structured to meet the scale of the crisis, both to efficiently deliver resources and to ensure that resources are distributed equitably, reaching the low-income renters of color who were both hardest hit by the pandemic and already housing insecure before Covid-19. Renters also need stronger eviction protections, including access to free legal assistance and eviction diversion programs. States and localities should extend their eviction moratoria until the pandemic rent debt crisis has subsided.

As they design rent relief programs, local and state policymakers should implement policies that adhere to the following equitable, common sense principles:

- No renter, regardless of immigration status, should be evicted or burdened with years of debt for rent that they were unable to pay during the pandemic.

- Rent debt due to the pandemic should be fully forgiven and should not be conditioned on landlords’ acceptance of funds or participation in programs.

- Financial assistance to landlords should address the fiscal needs of landlords in danger of going out of business due to lost rent, with a particular focus on keeping small community-based landlords and nonprofit affordable housing operators solvent, rather than attempting to achieve full rent replacement for all landlords. California’s program, negotiated with the state’s landlord association, provides an example: landlords receive 80 percent of back rent owed.

- Local municipalities’ authority to pass stronger eviction and debt protection laws should be preserved.

- Landlords should continue to fulfill their legal obligations to tenants regardless of whether they receive assistance, including the duty to maintain habitable premises, refrain from harassment and retaliation against tenants, and respecting tenants’ legal rights.

For more local policy ideas and examples, see https://ourhomesourhealth.org

* The number of renter respondents to the Pulse survey for Arkansas, Delaware, Maine, Mississippi, North Dakota, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming was insufficient to produce reliable data to include in the dashboard.