New index reveals significant racial inequities even in the most prosperous cities and metros; provides data to help leaders develop targeted strategies for inclusive prosperity

By Sarah Treuhaft, Abbie Langston, Justin Scoggins, Joanna Lee, and Manuel Pastor

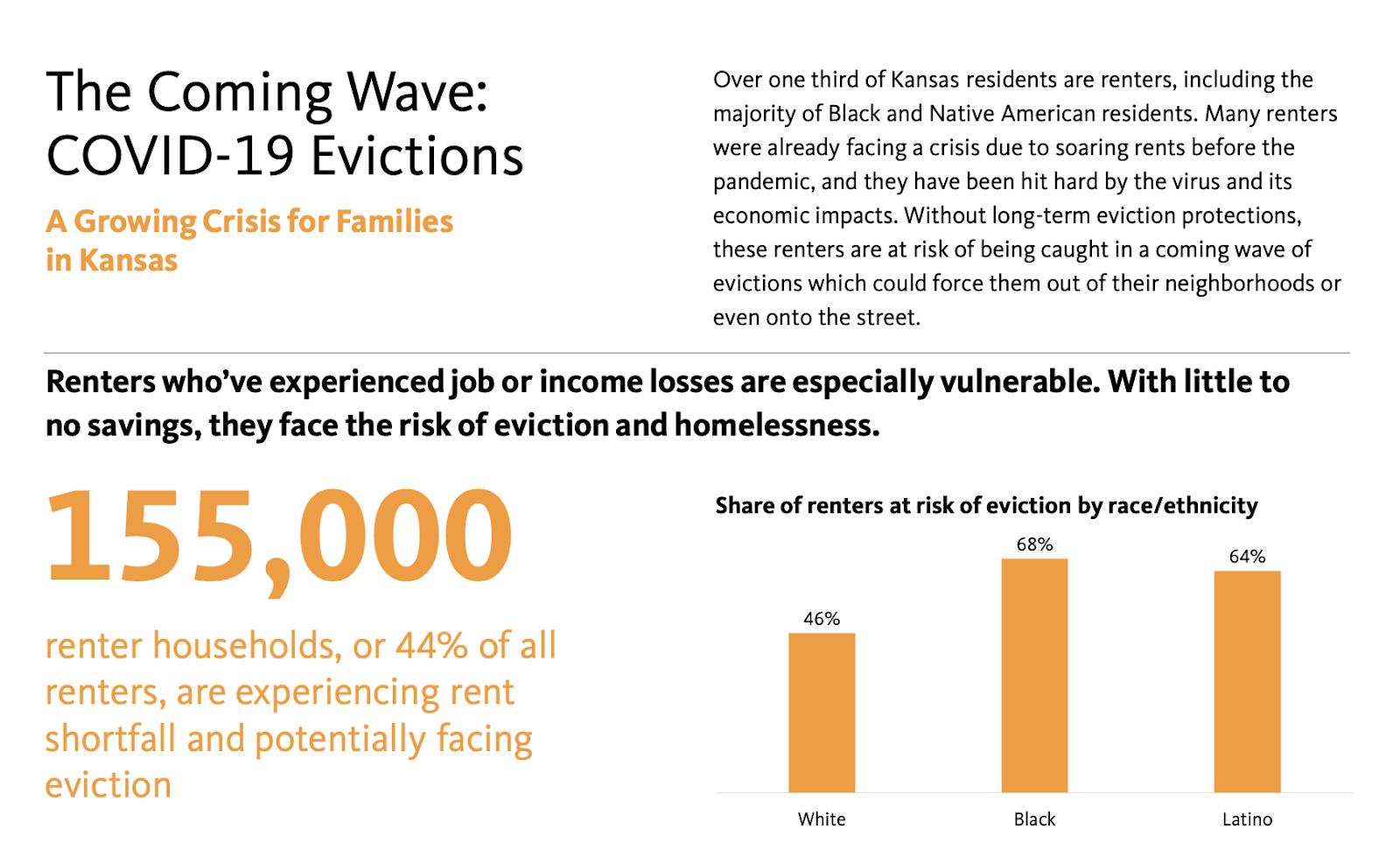

Racial equity is the defining issue of our time. The brutal murder of George Floyd — amidst a pandemic disproportionately harming the health and livelihoods of Black, Latinx, and Indigenous people — put dismantling structural racism at the center of our national policy debate.

Against this long overdue nationwide reckoning, community leaders are searching for policy solutions that can transform systems and structures and make meaningful progress toward racial equity. Disaggregated data at the local level is crucial to this endeavor: achieving equity requires targeted solutions that address structural and institutional racism, eliminate the barriers that prevent people from thriving, and provide the resources and opportunities that people need to reach their full potential. And data that reveals which groups are being excluded, by how much, and in what policy areas is an essential ingredient to develop effective strategies that match the scale of the challenge.

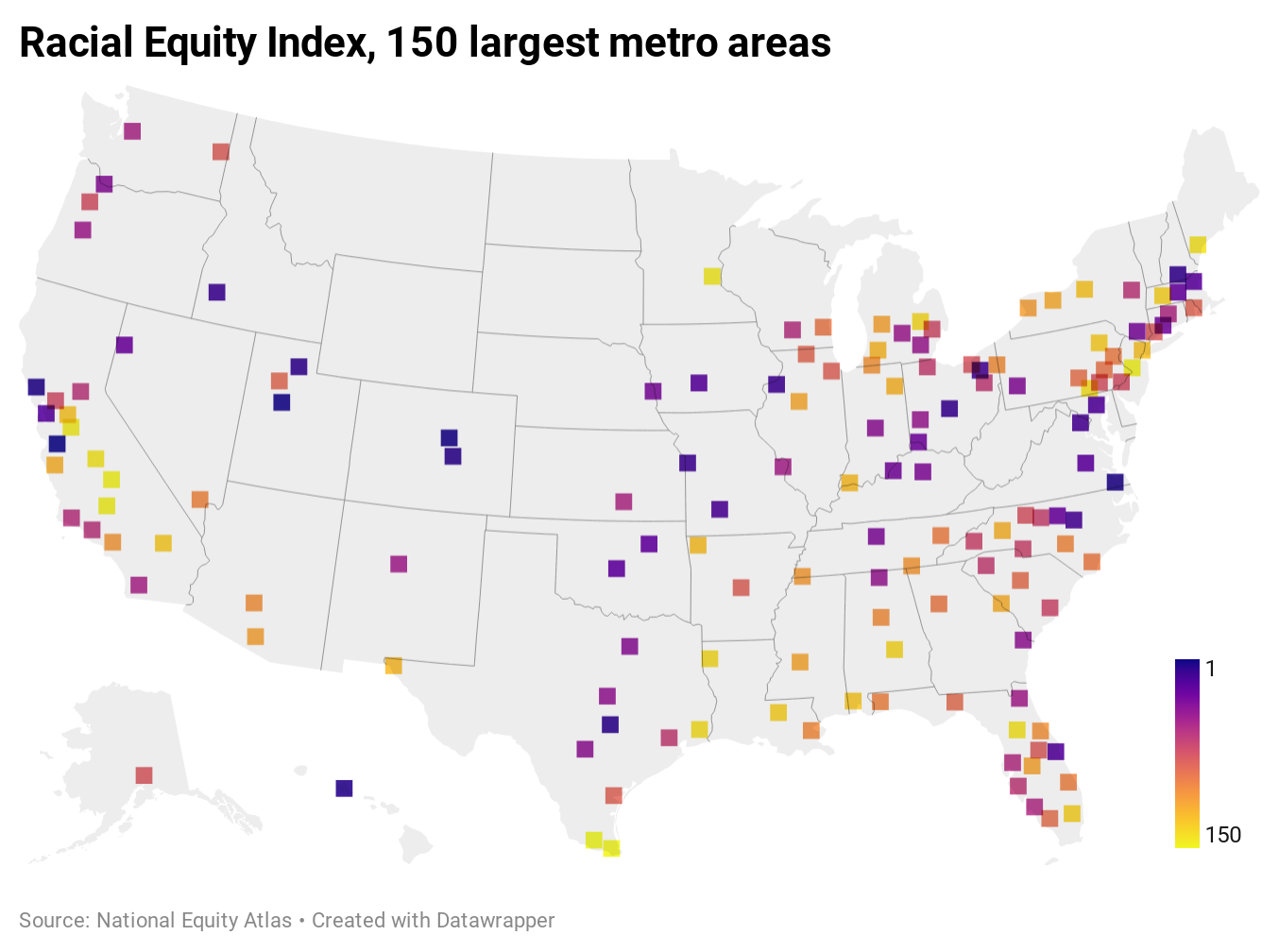

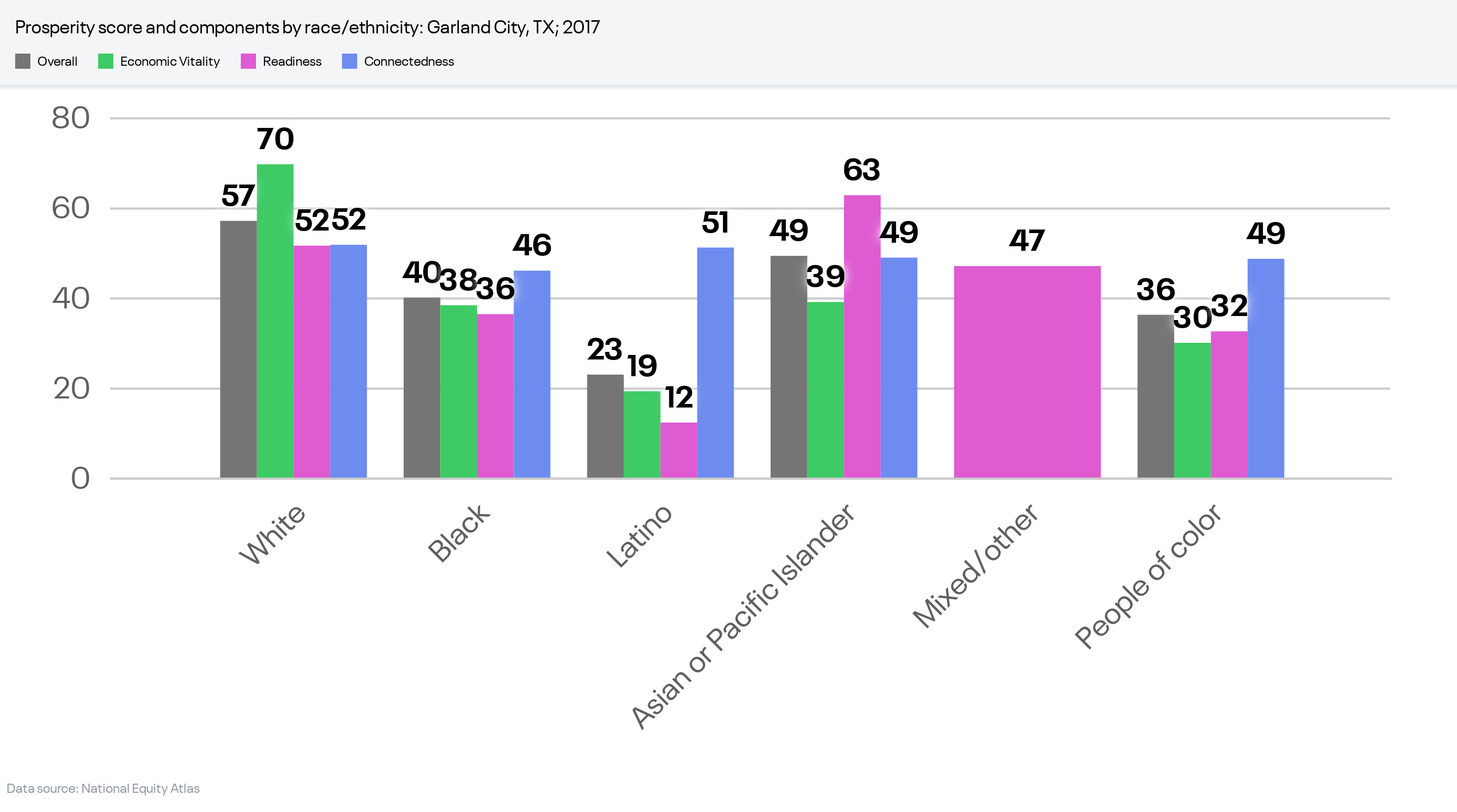

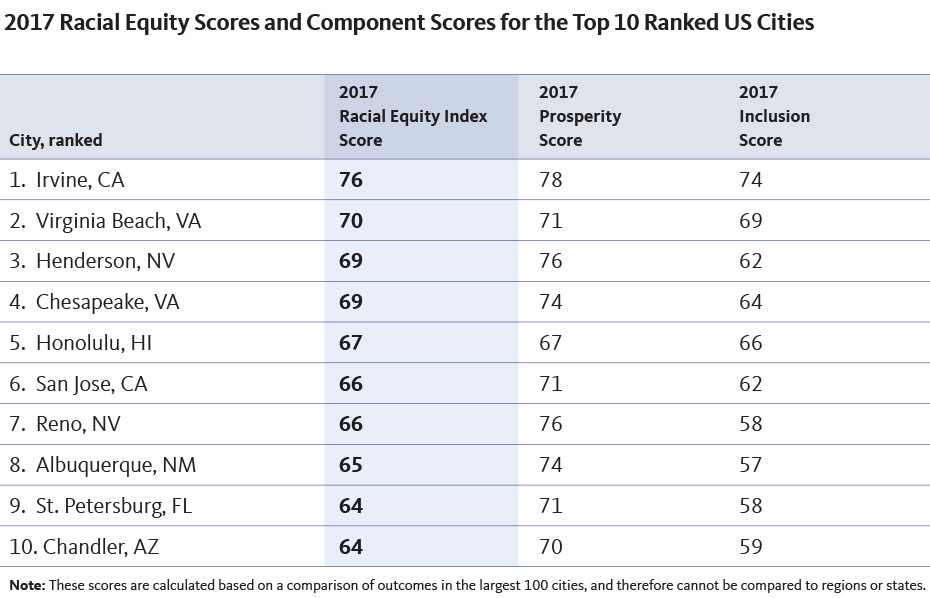

The Racial Equity Index is the nation’s first-ever tool designed to support communities in advancing equity solutions by measuring the state of equity in the 100 largest U.S. cities, the 150 largest metros, and all 50 states on key indicators of prosperity and inclusion by race. The Index is an integrated and holistic measure to compare the state of equity across different places, developed in response to the demand for a more comprehensive, summary picture of how communities were doing on our equity metrics. It provides a snapshot of how well a given place is performing on racial equity compared to its peers — comparing cities to cities, regions to regions, and states to states. Because equity means both closing racial gaps and ensuring that everyone is doing well, the Racial Equity Index is based on two components: an inclusion score that indicates the extent of racial gaps in outcomes for a series of nine equity indicators (wages, unemployment, poverty, educational attainment, disconnected youth, school poverty, air pollution, commute time, and housing burden) and a prosperity score that indicates how well the population is doing overall on those same indicators.

This analysis shares insights from our analysis of the Index for cities and metros. Please see Introducing the Racial Equity Index to learn more about the Index and how to use it and explore the data for your community with the Index data tool.

Key findings from the Racial Equity Index include:

-

Every community is hindered by systematic racial inequities. Even in the best-performing places on the Index, there are significant and preventable racial inequities.

-

Inclusive prosperity remains elusive among America’s metros and cities. It is very rare for communities to have high levels of prosperity, in terms of overall performance on the indicators, and high levels of inclusion, in terms of low racial disparities.

-

Robust economic growth alone does not bring about racial equity and inclusion. While some of the regions with the most dynamic economies perform well on the Index, overall there is a weak relationship between traditional measures of economic development such as job growth, and racial equity and inclusion.

-

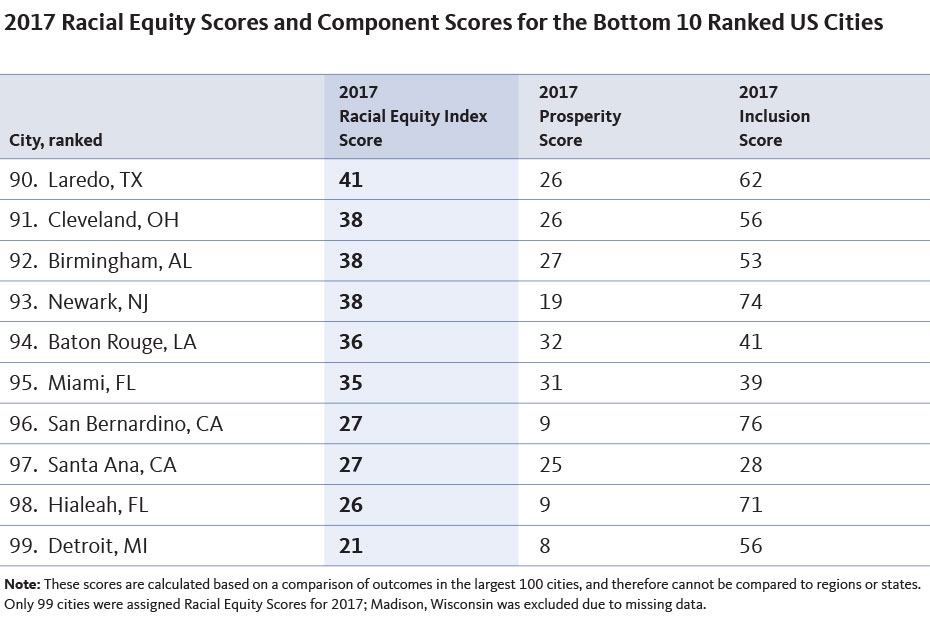

Achieving racial equity requires improving conditions in the population centers where most people of color live. Few of the cities with the largest Black and Latinx populations perform well overall on the Index or on Black or Latinx prosperity.

-

Racial equity is not a zero-sum proposition. Most of the cities and regions with the best outcomes for communities of color also have good outcomes for their White residents, and vice versa.

Each of these is further described below.

1. Every community is hindered by systematic racial inequities.

The Index reveals just how far all cities and metros have to go to correct systems that are perpetuating racial inequities. Because it is a relative Index, even places that are the top performers have significant racial inequities.

Take the region of San Jose, California. The tech epicenter has the highest score on the Racial Equity Index because of its strong overall performance in terms of wages, poverty, educational attainment, and school poverty and relatively lower racial disparities on indicators of air pollution, commute time, educational attainment, and unemployment.

Yet, there are large racial inequities in San Jose. For example, even with the highest share of Black college graduates of any region (37 percent), there is a 23 percentage point Black-White disparity in terms of educational attainment, and the White-Latinx disparity is 44 percentage points (60 and 16 percent, respectively). And among college graduates, Black and Latinx workers earn $12-$17 less per hour than White and Asian or Pacific Islander workers. Note that while the regional median wage for the Asian or Pacific Islander population as a whole is $43, median wages vary significantly within that group

2. Inclusive prosperity remains elusive among America’s metros and cities.

Equitable communities both have strong overall performance on indicators of well-being and low racial disparities, which is why the Racial Equity Index combines a prosperity score and an inclusion score. But what we see is that very few places are both doing well on prosperity and inclusion.

The metros that have the best overall performance on the indicators are not the most inclusive and tend to have wide racial disparities. Among top 25 regions on the prosperity score, none are also in the top 25 on the inclusion score, and only seven even make the top 100 on inclusion. Eighteen of them are in the bottom 50 on inclusion, including the Minneapolis-St. Paul region, which has the sixth highest prosperity score, but is second from the bottom in terms of its inclusion score.

3. Robust economic growth alone does not bring about racial equity and inclusion.

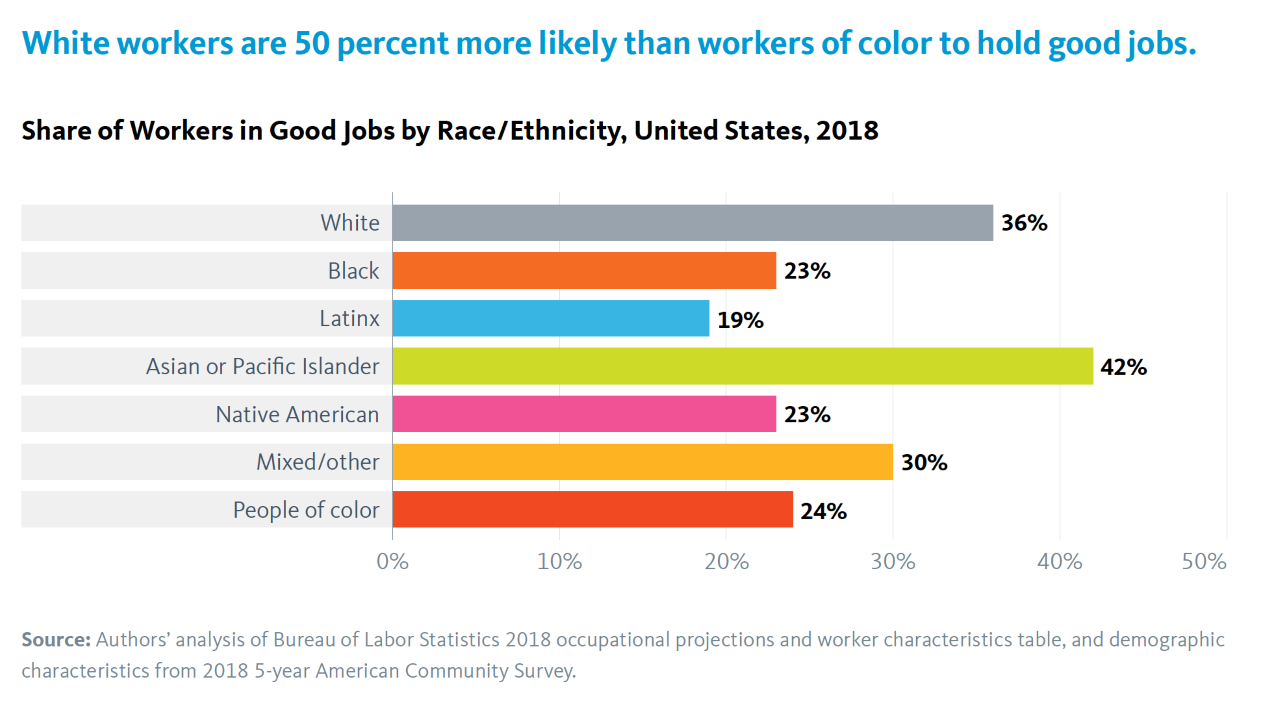

Over the past decade coming out of the Great Recession, growth in jobs and economic output has been concentrated in a small number of large metros, and within those places economic gains have largely gone to investors, corporations, and a small number of highly-educated knowledge economy workers.

A look at post-recession job growth in regions in relation to the Racial Equity Index underscores the weak relationship between job growth and racial equity. While there is some correlation between job growth and racial equity performance, with some high-growth metros like Austin, Denver, Raleigh, and San Jose performing well on the Index, the connection is not strong. Similarly, strong job growth does not drive positive outcomes for Black and Latinx residents. Of the 25 metros with the highest post-recession job growth, only seven of them were among the top 25 regions on prosperity for Black residents (Austin, Denver, Dallas, Fayetteville, Raleigh, San Jose, and San Antonio). And only three of them were among the top 25 regions on prosperity for Latinx residents (San Francisco, Austin, and Provo).

4. Achieving racial equity requires improving conditions in the population centers where most people of color live.

About 29 percent of Black people in the United States live in just 50 cities, underscoring the importance of integrating place-based and people-focused solutions to advance racial equity. The concentration of different racial/ethnic groups in certain regions, cities, and neighborhoods is in large part a consequence of systems and policies that produced and reinforced racial segregation — and the persistence of inequities in those places follows from a long history of disinvestment and deprivation. Some of the highest scoring cities on the Racial Equity Index have the smallest Black populations: In seven out of the top 10 performers, the Black population is significantly underrepresented compared to the national share (Albuquerque, Chandler, Henderson, Honolulu, Irvine, Reno, San Jose). Similarly, the Latinx population is underrepresented in six of the top 10 cities on the Index (Chesapeake, Henderson, Honolulu, Irvine, Virginia Beach, St. Petersburg).

Of the 12.9 million Black people living in the largest 100 cities, about 80 percent of them live in the 33 cities with at least 100,000 Black residents. Only two of these cities are among the top 20 performers on the Racial Equity Index (Nashville and Norfolk), and 10 are among the bottom 20 performers (Atlanta, Baton Rouge, Birmingham, Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Houston, Memphis, Newark, and New York). Only two — Durham and Raleigh, which are in the same region — are among the top 20 performers for Black prosperity, and wide racial gaps in prosperity are evident in these places:

Similar trends hold for Latinx people. Among the 41 cities with at least 100,000 Latinx residents, only two (Albuquerque and San Francisco) rank in the top 20 prosperity scores for the Latinx population, while 12 (Charlotte, Dallas, Fresno, Hialeah, Los Angeles, Milwaukee, Oklahoma City, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Bernardino, Santa Ana, and Newark) are in the bottom 20.

The cities with the best outcomes for Latinx residents tend to have relatively small Latinx populations: among the top 20 performers on Latinx prosperity, nine were among the 20 cities with the smallest Latinx populations and only five have Latinx populations at 50,000. The same dynamics are found at the regional level.

In the 25 regions with the largest Latinx populations, only two ranked in the top 25 for regional prosperity scores on the Racial Equity Index (Boston and San Jose), and just three were among the top 25 performers for Latinx prosperity (Austin, San Francisco, and Washington DC). Even among those best performers, Latinx residents still face significant racial inequities on key indicators of prosperity.

5. Racial equity is not a zero-sum proposition.

Looking at the prosperity scores across racial/ethnic groups, we find that most of the cities and regions with the best outcomes for communities of color also have above-average outcomes for their White residents, and vice versa. Of the top 20 cities for prosperity for people of color, for example, all but two of them are in the top 40 for White prosperity, all but one are in the top 40 for Black prosperity (among the 16 with large enough Black populations to generate Black prosperity scores), and all but one are in the top 40 for Latinx prosperity.

And of the top 20 cities for White prosperity, six — Anchorage, Austin, Denver, Durham, Plano, and Raleigh — are also in the top 20 for Black prosperity (among the 16 with large enough Black populations to generate Black prosperity scores) and six are in the top 20 for Latinx prosperity (Anchorage, District of Columbia, Irvine, Plano, San Francisco, and Scottsdale). Only one — Dallas — falls in the bottom 20 for both Black and Latinx prosperity.

Making Progress on Racial Equity Will Require Tailored and Bold Solutions

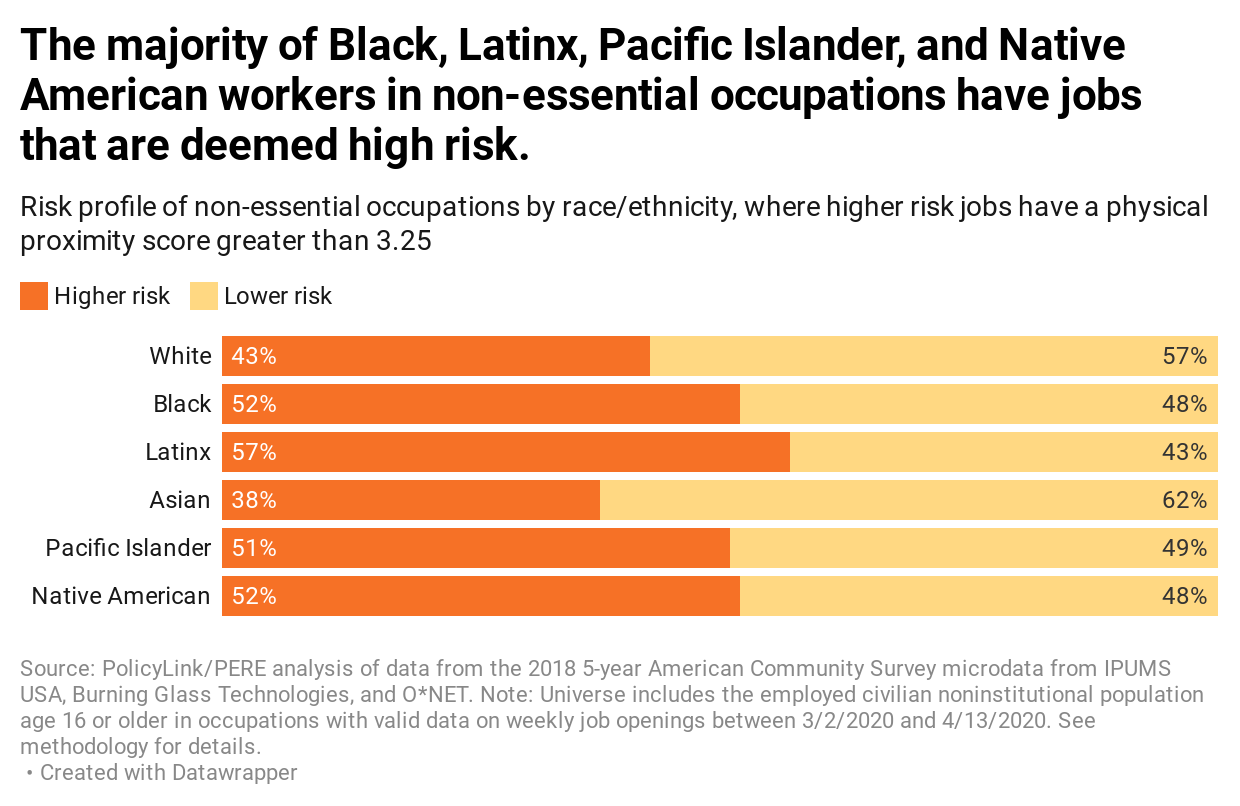

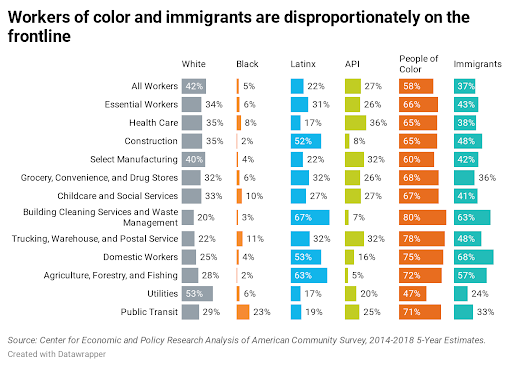

Our analysis of the Racial Equity Index for cities and metros reveals that even the best performing places exhibit significant racial disparities, and even the places with the most economic success post-recession fall short on equity. At a time when Black, Latinx, Native American, and Pacific Islander communities are the hardest hit by another recession, it is imperative that leaders at all levels recognize that targeted, race-conscious strategies are necessary to bring about an inclusive recovery. Doing so will create tremendous benefits that cascade up and out to the advantage of an entire community. Equity is the path to prosperity: By developing solutions that are informed by and effectively reach the people most impacted by structural racism and economic inequality, we can build an equitable, prosperous future economy.